Investment views

Transnet and the art of the possible

"The railway is one of the most potent factors in modern civilization, and its history is the history of human development." – John Moody, founder of Moody’s Investor Service

The Quick Take

- Ailing SOE Transnet is a drag on SA’s economic growth, slowing commodity exports and taking a toll on the road network and its users

- While different to SA’s Freight Logistics System, North American rail’s five-pronged PSR management system could guide recovery

- Restoring Transnet to full capacity, while challenging, would be significantly beneficial to the South African economy – boosting both productivity and tax revenue

- The Roadmap for the Freight Logistics System in South Africa lays out a new structure and steps to unlock Transnet freight rail efficiency.

Transnet is the second-largest State-owned enterprise in South Africa (SA) after Eskom. Unfortunately, its decline has been as staggering as its larger stablemate, with its 2023 financial statements showing that its performance deteriorated from a net profit of R5 billion in 2019 to a net loss of R5.7 billion in 2023. With over R120 billion in debt at the end of March 2023, Transnet’s ability to invest in much-needed infrastructure upgrades is highly constrained which, combined with its poor operational capacity, has choked the economy. Consultancy firm, the GAIN Group, has estimated that inefficient rail transport at Transnet could have cost the economy approximately R353 billion last year, mainly due to forfeited commodity exports.

AN INDUSTRY DISRUPTOR

The North American freight rail industry underwent a transformation starting in 2003, led by industry titan Hunter E. Harrison. During the course of his career, he served as CEO of three railways, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific and CSX, dramatically improving the operational and financial performance of each. He termed his system for managing freight railways precision scheduled railroading (PSR). Five out of six North American railroad operators have adopted PSR to manage their networks. These are well-run, attractive businesses, aspects of which could serve as a North Star to guide Transnet’s recovery.

One of Harrison’s key insights was that a fluid, reliable network would maximise the use of both the network and the rolling stock. Given the high capital costs to acquire and fixed costs to maintain rail assets, optimising utilisation is critical to lower the overall cost per carload. Simplistically, if you double the carloads of freight transported by a locomotive, you halve the capital cost per carload. The same goes for railway lines where significant capital must be spent for maintenance.

While it is all very well to have an insight on a piece of paper, Hunter Harrison executed the theory and demonstrated that it worked. He then, literally, wrote the handbook on how to execute PSR – “How we work and why: running a precision railroad”

In the book, he highlights five key principles to run a railroad well:

- Service – provide the service you commit to and only accept business that makes economic sense.

- Cost control – constantly improve processes to manage expenses and capital costs.

- Asset utilisation – unused rail assets incur costs and become a liability. Have the right asset base to match the operation and work to maximise utilisation.

- Safety – this is the responsibility of all employees and is critical when dealing with such heavy equipment. A safety-first culture avoids injury, anguish, and unnecessary expense.

- People – a railroad can’t operate without people. Build a team that communicates well, is resourced properly, and has leadership that leads by example and good things will happen.

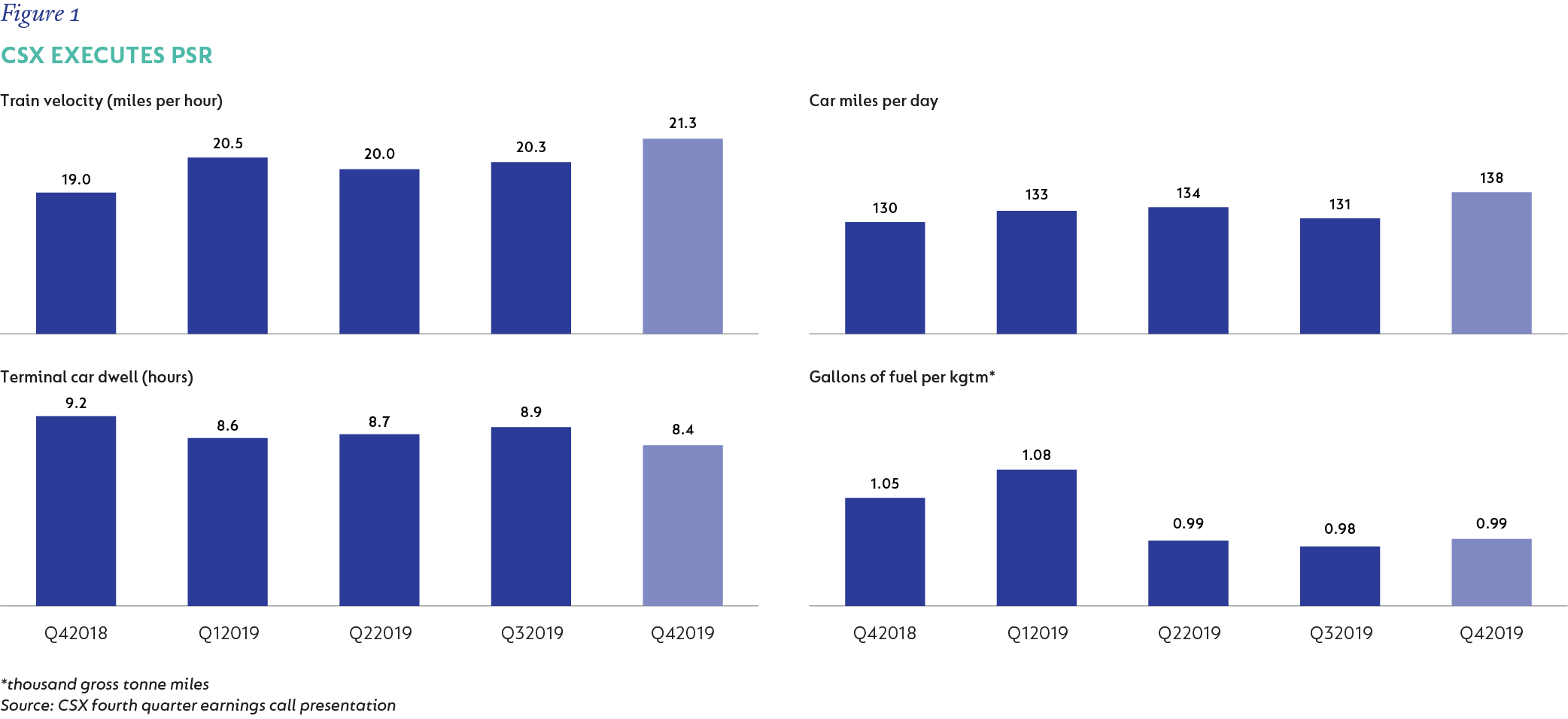

The system proved itself to be effective. Figure 1 illustrates how rapidly the transformation can occur. In 2017, CSX began implementing PSR and by 2018 it showed significant improvements in its operational metrics.

At CSX, the North American railroads that most recently undertook the PSR journey, and Canadian National, which had to refocus on PSR after losing its way, there were several common steps that took place at the initiation of the process. The CEOs first undertook a process to understand the current and future volume demand and economics of different commodities and routes. At CSX, current and potential customers were engaged to understand their transport requirements and routes that no longer made economic sense were culled. Employees were engaged and trained to understand that the schedule was the railroad’s defining operating system and that any changes needed to be coordinated with the schedule manager (as opposed to the other way around, which is often a cause of disruption to other traffic flows).

BRINGING TRANSNET BACK ON LINE

Restoring Transnet to its full operational capacity would have significant positive implications for SA and its citizens for a few reasons.

Rail transport consumes a quarter of the fuel used by road transportation, making it particularly attractive for transporting commodities and other goods over long distances. By removing heavy freight from roads, traffic volumes would be substantially reduced, as would the damage and cost to maintain the road network. From a social perspective, increased rail usage in SA would make our roads safer for all users and likely lower the cost of consumer goods through lower transport costs.

Transnet operates a nationwide freight rail network of approximately 21 000 route-kilometers, with access to seven port terminals. Given SA’s commodity-rich economy, we have excellent origin/destination pairs, with mines on one end and ports to the rest of the world on the other. The rail network also interconnects the large commercial hubs of Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and Gqeberha.

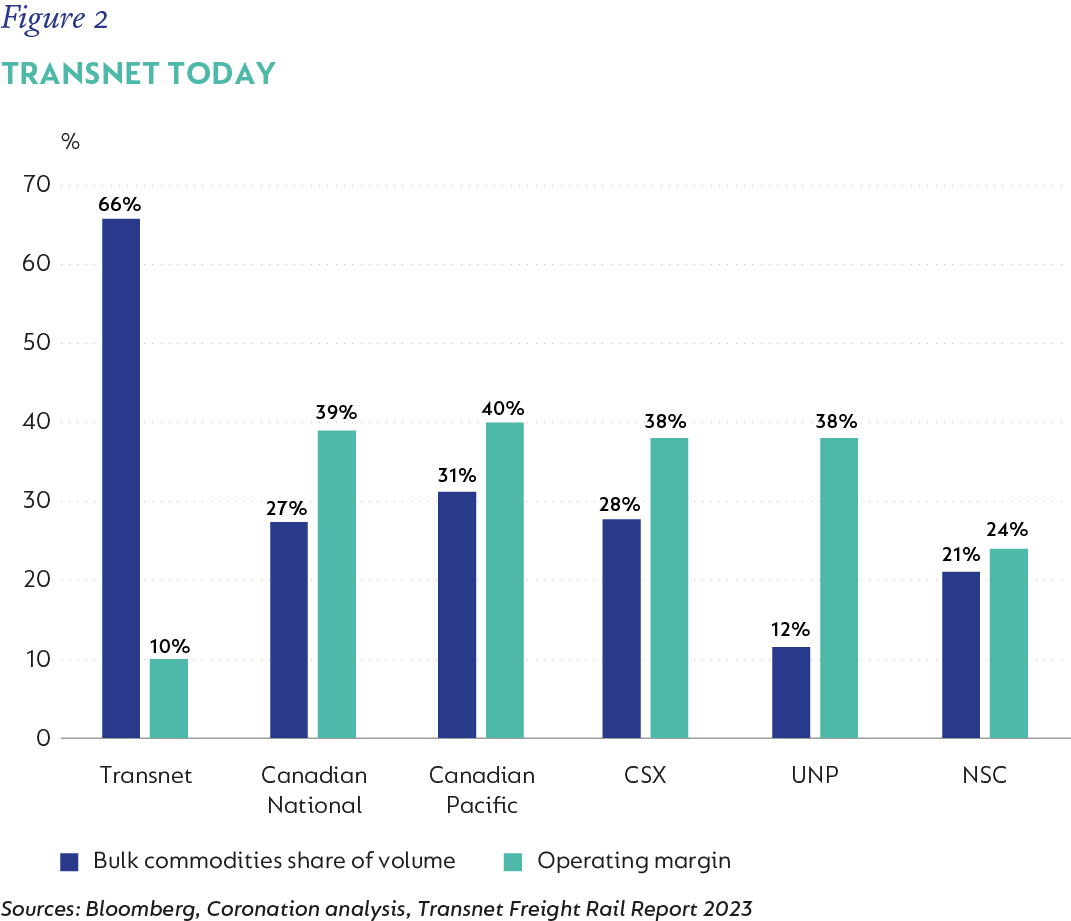

Figure 2 illustrates that railways with higher bulk commodity share are often more profitable than those with other types of cargo. Given that Transnet is a rail monopoly that transports a substantial volume of bulk commodities, it is potentially a physically and commercially significant asset. But only if operations can be improved.

However, based on the Draft Transnet Network Statement released in March this year, which provides a comprehensive overview of the rail network’s condition, there is a mammoth, but not insurmountable, task ahead for this potential to be realised. Transnet needs to stop the rampant theft and vandalism of rail infrastructure, repair ageing infrastructure and potentially increase the length of sidings to allow longer trains to operate.

PROTECTING THE ASSETS

Vandalism of substations and theft of overhead transmission equipment (mostly copper) in various parts of the freight network means that diesel locomotives are required on affected sections. In the critical Container Corridor that links Durban’s port to Gauteng and other inland destinations, a shocking 52% of substations were reported to be offline as a result. Further, the theft of signalling systems has led to manual authorisations and speed restrictions being implemented, creating excess expense, and reducing network capacity. Transnet will have to end the signalling and substation destruction in order to achieve a fluid network.

REVERSING DECAY

Lack of maintenance has taken a severe toll on SA’s rail network. In some areas, deteriorating track conditions have resulted in speed restrictions, also resulting in manual authorisations. Many sections are undergoing monthly maintenance for up to 12 hours a day and parts of the Northeast corridor have obsolete equipment and freight yards with poor drainage, wasting further valuable capacity and slowing operations. To add to these challenges, the crucial Container Corridor that links the Durban port to Gauteng was still undergoing maintenance to recover from the KZN floods when the Transnet assessment was published. The Transnet Freight Rail Report shows that last year, R1.7 billion in capital was allocated to repairing flood damage. For SA’s rail operator to thrive, investment in infrastructure is essential to ensure efficient use of its assets which is a key PSR principle.

INCREASING EFFICIENCY

Relatively short rail sidings (a section of spare track allowing one track to pass another) restrict train length on several lines. Increasing train length is one way that Hunter Harrison’s PSR networks lower the cost per car (adding cars to a locomotive is a cheaper way to increase capacity than adding locomotives). If investments are made to extend sidings, Transnet could run longer trains and reduce the locomotive cost per carload of freight.

REASON FOR OPTIMISM

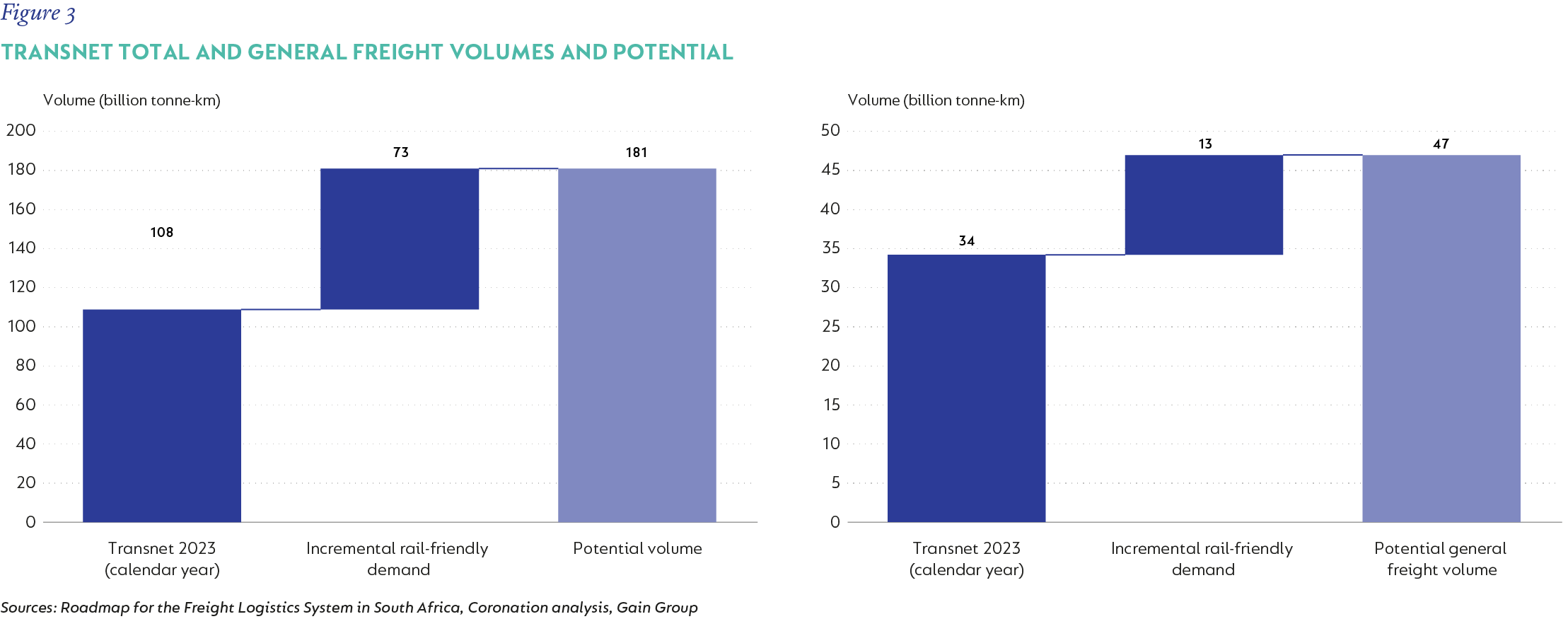

In spite of the considerable headwinds to Transnet’s recovery, all hope is not lost. Figures 3a and 3b show that potential volumes were nearly 68% higher than actual volumes in the 2023 calendar year, and, more specifically, potential general freight volumes (all rail cargo excluding export iron-ore and coal) were 38% higher than those actually transported.

SA’s Roadmap for the Freight Logistics System contemplates sweeping changes in the operation of the freight rail network. Transnet’s freight rail operations are to be separated into an infrastructure manager (IM), responsible for investment into the rail network, and train operating companies. Importantly, third parties will be allowed to operate trains on the network.

Additionally, provisions will be made to allow private investment into rail infrastructure, through concessions, with legislation that governs allowable returns and access. Private sector investment in rolling stock is also encouraged. This will alleviate a big constraint to increased rail usage and reduce the capital draw on Transnet. However, it requires the IM to provide private investors with assured rail access with a duration that is long enough to warrant making long-lived asset investments. Expanded private sector investment in rolling stock also has the potential for job creation and skill development.

An important step considered in the Roadmap is the rightsizing of the network. This is essential in order to achieve a better trade-off between freight volume and the cost of maintenance than is currently the case, with many very low-density lines being uneconomical to operate. This makes a lot of sense and, as discussed earlier, is often one of the steps PSR networks undertake.

SA’s proposed model is distinct from the vertically integrated North American version, where the freight rail companies own both the networks and operate the trains. A vertically integrated model likely lends itself to easier coordination between the schedule manager and those operating the trains. To optimise SA’s rail network, Transnet will have to work closely with the train operators to develop schedules and align efforts when resolving operational issues that could have network-wide knock-on effects. Despite these differences, the five principles that Hunter Harrison identified are still highly applicable in SA.

The Roadmap lays out the steps to achieving a well-run freight network, even if we have to resolve some basics first. Crucially, government needs to back the management team fully for it to implement the Roadmap. A well-oiled freight rail network will then deliver for all South Africans, in the form of lower transport costs and a more competitive cost structure for industry. This, combined with the increased exports from a functional rail system, would see stronger GDP growth and tax revenue for the fiscus, a win-win for all those involved.

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional