Investment views

Bond Outlook

‘Keep your eye on how much the government is spending, because that is the true tax’ – Milton Freidman, economist

The Quick Take

- The Trump administration has injected heightened uncertainty as to the trajectory of assets in the coming year

- Escalating global debt poses a significant risk to economic prosperity across all markets

- The SARB’s intent to revise SA’s inflation target down is ill-timed and could be a headwind to SA’s nascent recovery

- The jury is still out as to whether the renewed optimism attributed to SA’s coalition government is warranted

2024 was another impressive year for risk assets, as continued strength in the US economy and market saw developed market equities deliver jaw-dropping, high double-digit returns. Conversely, developed market bonds grappled with sticky inflation and unease about excessive government borrowing. The return of President Donald Trump this month introduces uncertainty around the direction of US policy, casting a shadow over expected returns for the coming year.

2025 is the year of the Snake, which is believed to bring transformation, renewal, and growth. In a world that has been fractured by increasing geopolitical tensions and growing inequality, global debt has steadily increased to c. US$100 trillion and is expected to hit 100% of global GDP by the end of the decade. This is the shackle that needs to be shed for the world to enjoy transformative prosperity.

The US dollar powered ahead in the last few months of 2024, placing weakening pressure on most emerging market currencies. The rand ended the year at R18.84/US$1, which is -2.55% weaker than at the start, despite being up c. 6% by the third quarter of the year. Despite this, the rand was still among the top performers in the emerging market universe. The FTSE/JSE All Bond Index (ALBI) was up 17.18% over the year, following a 100 basis point (bps) rally in bond yields over the same period, with the longer end of the curve (>12y maturity) producing a return in excess of 20%. Inflation-linked bonds (ILBs) significantly underperformed cash (8.21%) and bonds over the period, delivering a paltry return of 7.77%. This was primarily due to a slower path to a normal real policy rate, despite inflation ticking down much faster than expectations. Global bonds had a poor year as global yields climbed, with US yields up 50bps and the FTSE World Government Bond Index returning -2.87% in US dollars and -0.01% in rands. South African (SA) bond outperformance was primarily due to the coalition of the Government of National Unity (GNU) in the middle of the year. This cooperative alliance helped reduce the local risk premium but will weigh on prospects for 2025.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF OUR INFLATION TARGET

In SA, we have become accustomed to disappointment, either due to underestimating incurred damages or an inability to push through needed reform timeously. However, our shining light in the economic wilderness has been the South African Reserve Bank (SARB). The SARB maintained its independence and institutional credibility when everything was crumbling around it in the Zuma era. It is an institution that is filled with principled individuals of the highest caliber, who have performed their duties admirably. Unfortunately, in the last year, their pursuit of a lower inflation target at a point in the economic cycle when lower borrowing costs could aid a tepid recovery has been ill-timed.

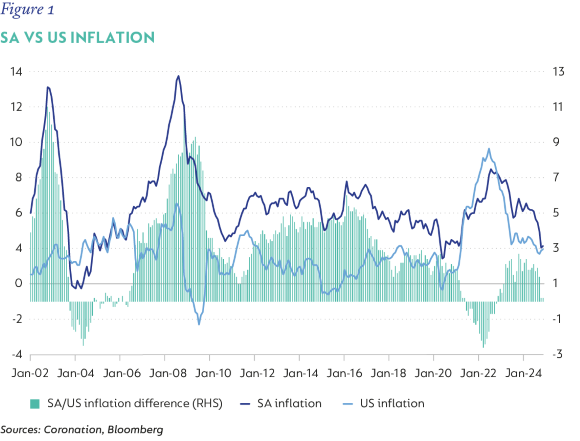

One of the key arguments from the SARB has been that the current inflation target has remained too high relative to the rest of the world. However, there are two key rebuttals that question the durability of the SARB’s case. Firstly, although many emerging markets have lowered their inflation target over time to a target that is below our 4.5% target, they have failed to sustainably maintain their inflation at that level. Secondly, the SARB has argued that our real policy rate needs to increase in line with the global real policy rate. However, as global inflation has remained high, ours has remained contained, narrowing the inflation differential significantly, thus reducing our need to track the global real policy rate higher. Figure 1 shows SA inflation relative to the US. It clearly illustrates that our inflation differential has narrowed from an average of 4% pre-pandemic to 2% post-pandemic.

SA inflation will average at around 4.5% in 2024 and 4.2% in 2025, before ticking back up to an average of 4.9% in 2026. This provides the SARB with room to ease policy rates further to 7.25% by the second half of 2025. However, given that the SARB is likely targeting inflation lower than 4.5% (probably closer to 3.5%), it is unlikely rates will remain there for very long, especially in light of the uncertainty about the path of US policy easing due to the inflationary impact of the Trump administration’s policy shift. Our forecasts see a reduction in the SA repo rate to 7.25% by the end of the first half of 2025, which aligns with market pricing. However, if an official change in target is communicated during the course of the year, the policy rate could revert to current levels, as per market pricing. We do believe that if the target is changed in 2026, the measurement date will be set for 2028, which would offset the need for an imminent move higher in the repo rate.

A HEAVY BURDEN

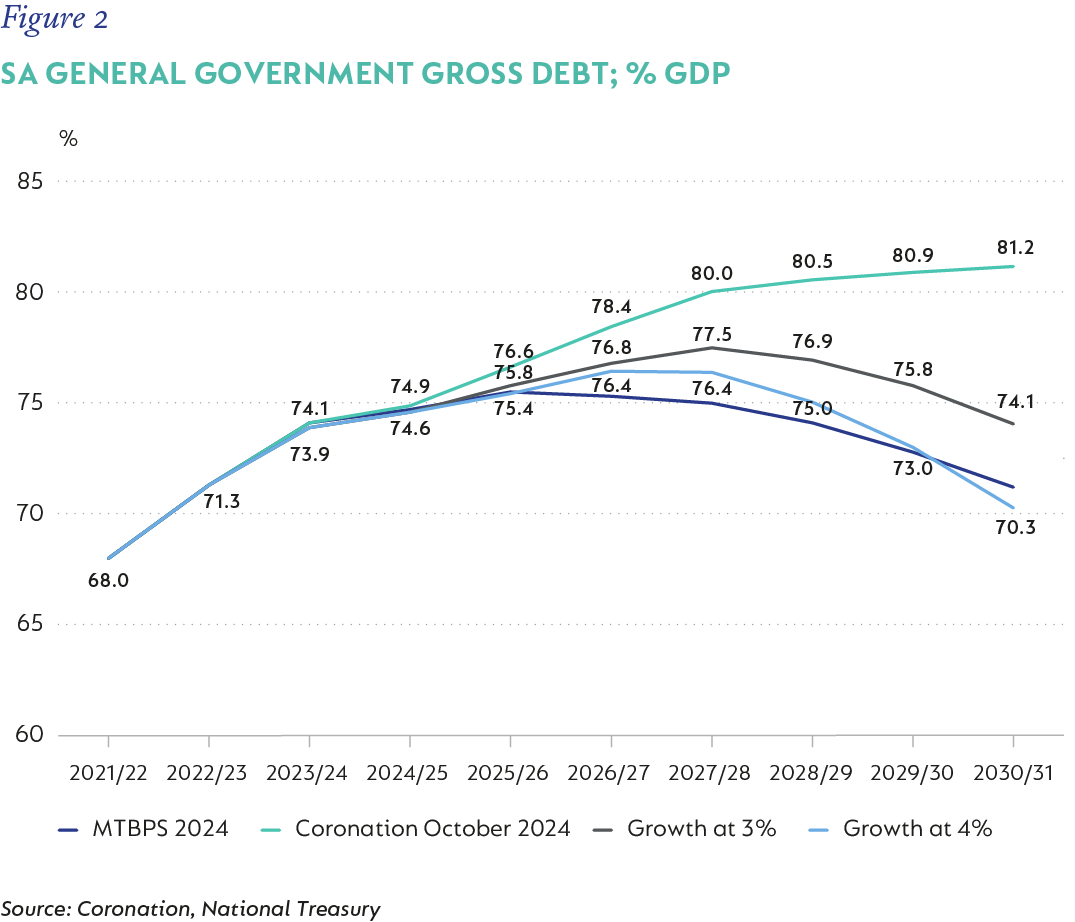

Fiscal policy remains the Achilles Heel of the SA economy. The debt load will continue to increase towards 80% of GDP as acknowledged, but unaccounted-for items continue to weigh on government expenditure. These include further support for State-owned enterprises – Transnet more immediately and an increasing probability for Eskom if higher tariffs are not granted or municipal debt is not repaid, municipal infrastructure upgrades, a larger wage bill, and high debt service costs. The only silver bullet is higher economic growth. Unfortunately, due to the slow pace of previous reform implementation, the magnitude of real economic growth that is required in order to stabilise and then reduce the debt load is around 3% to 4% (Figure 2). This is still some way off from our growth expectation of 2% to 2.3% by 2026, which is heavily dependent on the sustainability of the GNU. As such, although the noise around the fiscal trajectory has quietened for now, the risks posed to the economy if implementation falters or growth fails to recover over the next two to three years are still very high.

SOME CAUSE FOR OPTIMISM?

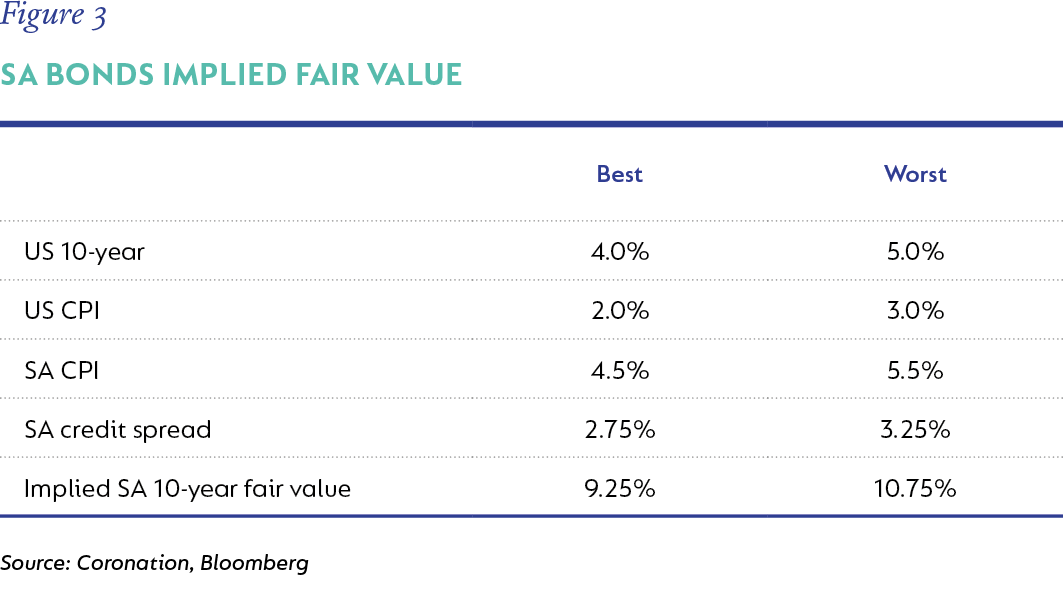

SA government bonds (SAGB) spent half of last year languishing at the bottom of the performance table before turning course in the second half of the year following an unexpected positive turn in the SA political landscape. However, the jury is still out as to whether the ship can change course and do so swiftly. The risk premium in SA bonds has reduced significantly and, although absolute levels remain high at around 10% in the 10-year SAGB relative to global bond yields and other assets, SA bonds seem well priced for their underlying risks. Our bond fair value stack (Figure 4) puts current trading levels marginally on the cheaper end of the fair value trading range.

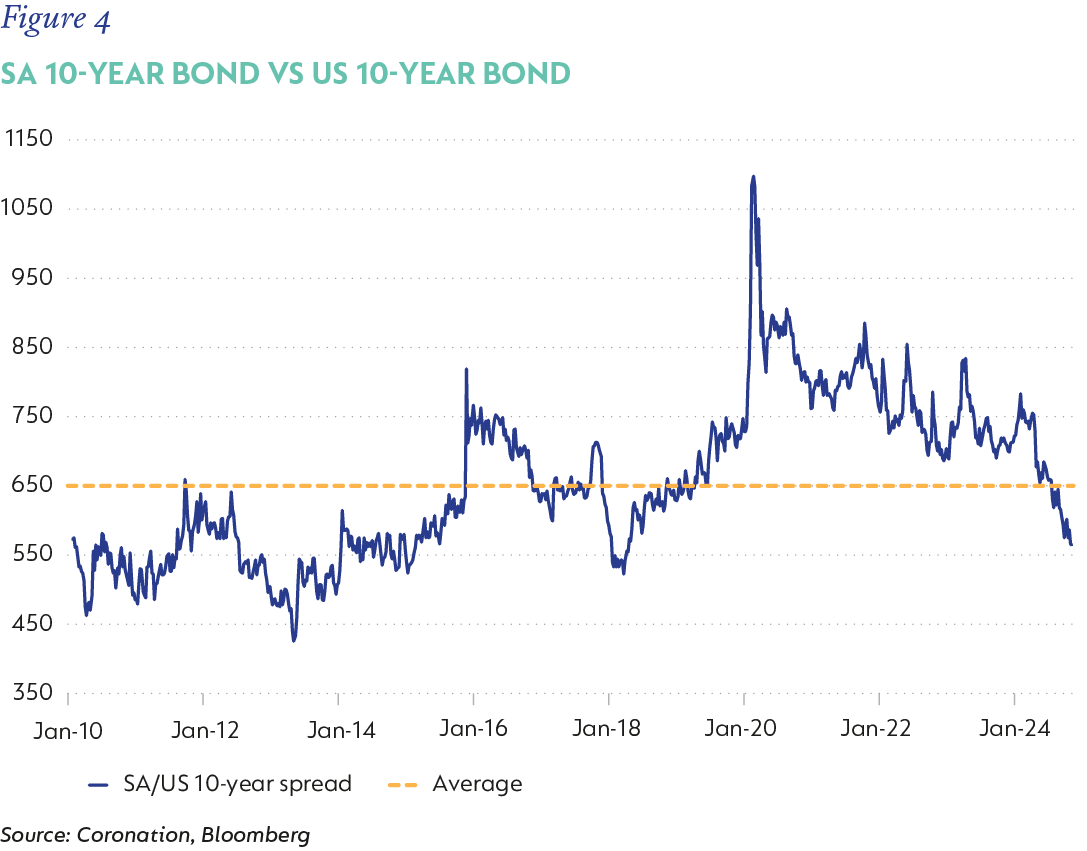

US bonds have sold off by 50bps over the last year despite SA bonds rallying by 100bps, which tightened our trading spread over the global risk-free rate (Figure 4). In large part, the risk premium was initially too aggressive, but the current trading levels have brought SA back to levels last seen when it was an investment-grade country, which suggests the market hopes for a more optimistic outcome.

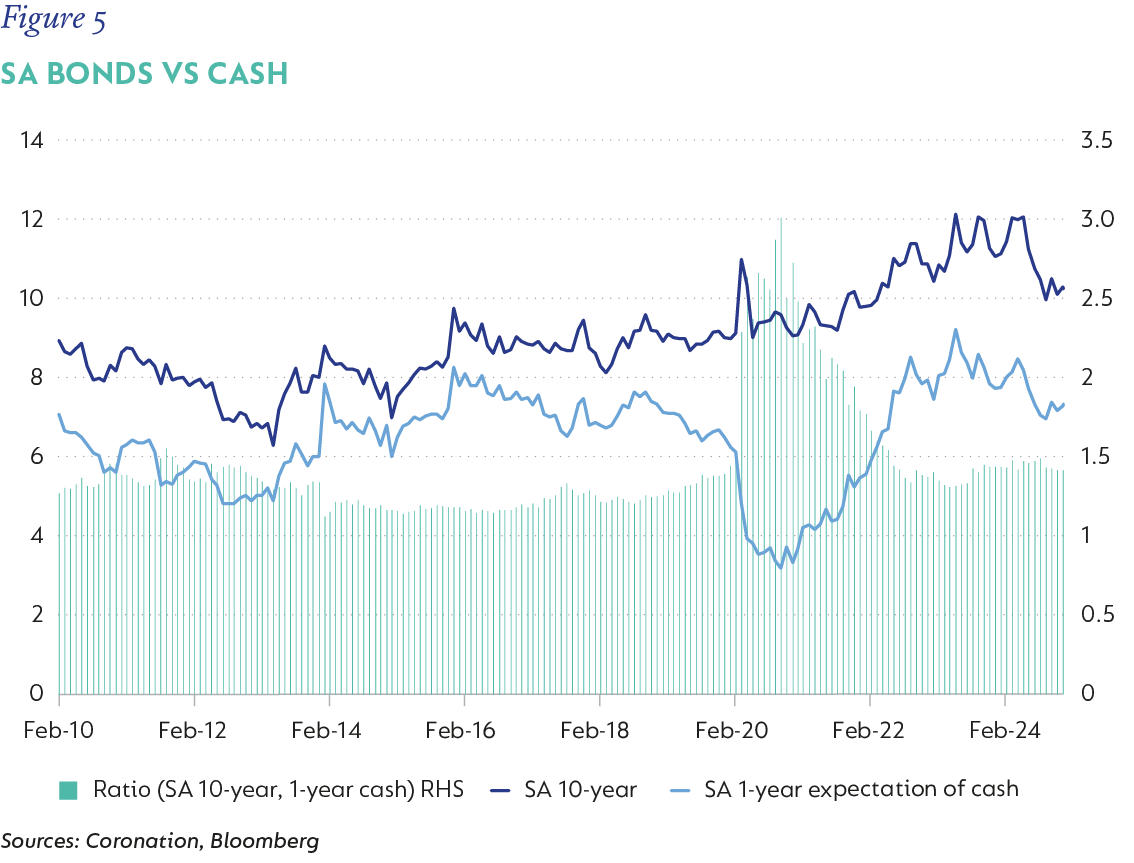

SA bonds offered quite a significant pickup relative to cash coming out of Covid, which was indicative of the large amount of protection in yields that were on offer relative to cash, with bond yields trading at some points twice cash levels. However, in the last 18 months, cash has risen and bond yields have compressed, pushing the ratio between the SA 10-year bond yield and cash back to the long-term average (Figure 5), further indicating a reduction in yield protection and more sanguine market expectations.

UNCERTAINTY PREVAILS

The absolute level of bond yields is still attractive given their long-term trading history, however, the risk premium and protection offered by these bond yields have reduced significantly leaving them, at best, at fair value if not slightly overestimating the SA turnaround. In addition, the world is entering a very uncertain period in which global borrowing levels are at all-time highs, with global yields at risk of pushing higher given the possible change in policy given recent geopolitical developments. As such, local bond investors, need to remain vigilant in a landscape of increasing risk.

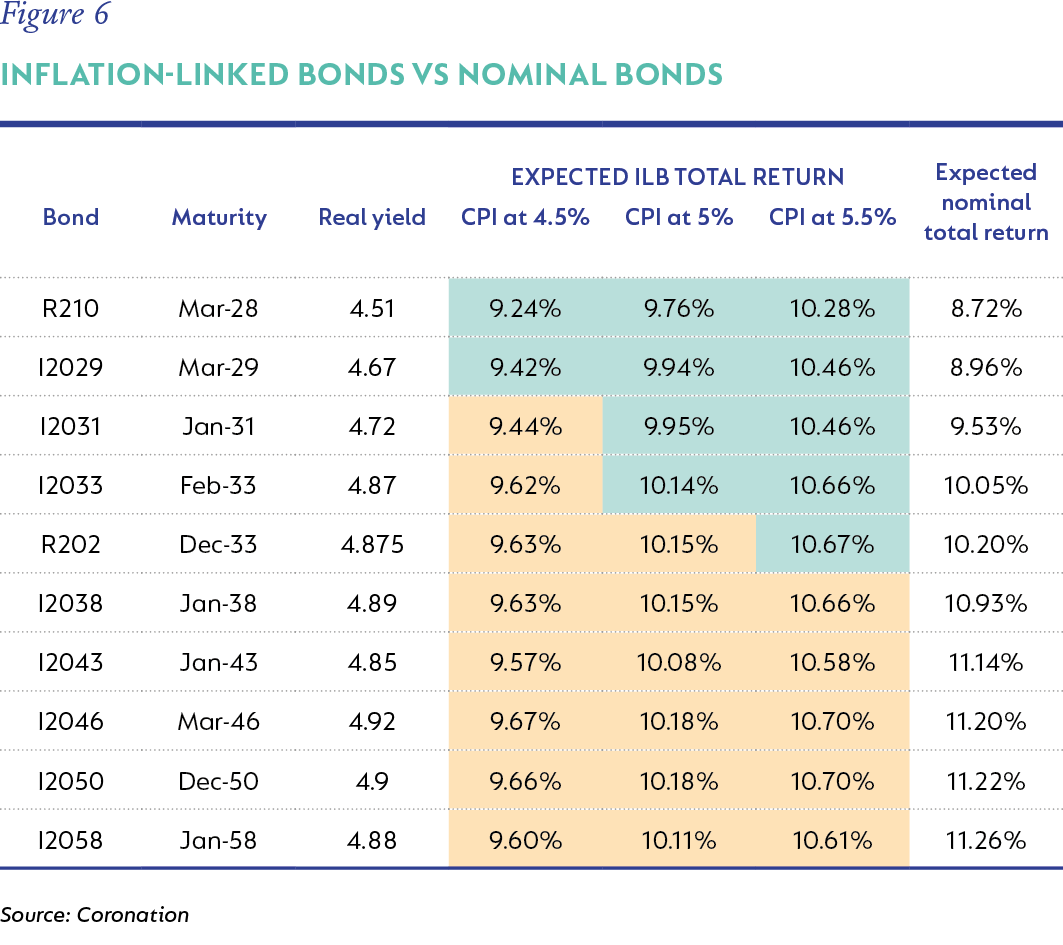

ILBs have been the worst-performing asset class within fixed income for the last couple of years. In a portfolio of assets, one requires diversification and something that offers insurance in the event the base case doesn’t materialise. As such, just because an asset has not performed well does not mean it does not deserve a place in the portfolio. ILBs are such an asset class, primarily because of their inherent risk-offsetting attributes and current valuation. ILBs offer protection if inflation materialises higher than expectations. At current levels, the real yields on offer are historically high (in excess of 4.5% across the curve, which implies a guaranteed return of CPI + 4.5%), and the total return on offer relative to nominal bonds remains attractive. This attractiveness is focused primarily on maturities of less than four to six years, as indicated in Figure 6. The cells highlighted in green show where the total return of the ILB (under an inflation assumption) is greater than the total return on offer by the nominal bond. The front end of the curve remains a better alternative to nominal bonds, due to its lower modified duration (capital at risk).

Local credit spreads are at historically tight levels due to low levels of issuance and large swaths of capital looking for a home with reduced volatility. The use of structured products, such as credit-linked notes (CLNs), has become ubiquitous within the local market. This sector has grown exponentially over the last five years and has reached a market size of over R100 billion. However, only a third of this market reprices, creating an inaccurate representation of asset volatility and pricing. CLNs mask the underlying/see-through credit risk as the issuing entity (predominantly local banks) is seen as the primary credit risk.

The increased usage of CLNs has not expanded the pool of borrowers, rather it has only served to concentrate it. This is due to the ability to limit the volatility of these instruments by not marking them to market based on the underlying asset price movements. The combination of attractive yields and no volatility is an opportunity that few would pass up, unless, of course, transparency of pricing is important to the underlying investor. As a result, there can be significant unseen risks within fixed income funds. Investors need to remain prudently focused on finding assets of which the valuations are correctly aligned to fundamentals and efficient market pricing. Except for a few opportunities, we view the local credit market as unattractive relative to other asset classes.

Despite a wobbly end to the year, risk assets enjoyed a relatively strong 2024. SA government bonds shone as they outperformed their emerging and developed market counterparts. The road ahead is less certain. Inflation has remained well behaved and is expected to remain close to the midpoint of the current target band. However, the SARB’s reluctance to ease rates might prove to be a headwind to bond yields and the economy going forward. In addition, local growth has remained lacklustre, and the growth required to shed the burden of our current debt load remains much higher than expectations. The risk premium on SA bonds has been much reduced and is commensurate, if not too idealistic, with SA’s economic future. In addition, global risks remain high as the incoming US president’s policy direction might stoke inflation and push global bond yields even higher still. We continue to maintain a neutral position on local bond yields in light of their reduced risk premium, with very little exposure to local credit and a moderate allocation to ILBs given their attractive valuation and offsetting risk attributes.

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional