Stagflation intensifies

01 July 2013 - Chantal Valentine

It was a torrid quarter, both globally and in South Africa. The outcomes, in short, underlined the stagflationary environment facing South Africa. Local growth indicators, though not recessionary, continued to show a lacklustre growth background, and many forecasts (ours included) have been downgraded to well below 3% – some are even below 2% – for growth this year. However, there has been no concomitant downgrading of inflation expectations.

The principal reason is the further sharp weakening of the rand seen during the second quarter of this year, following indications from the US Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) that it was considering ‘tapering’ its quantitative easing (QE) programme later this year. This led to concerns that the liquidity support to risky assets would be withdrawn and saw a number of assets, including South African bonds and the rand, selling off. It’s worth mentioning that various idiosyncratic developments across a number of emerging markets (including widespread political protests in Turkey and Brazil) didn’t help much, i.e. it is not only the QE news that led to weakness. The steep decline in the rand (17.5% depreciation against the dollar in the first six months of the year) and continued demands for – and accessions to – relatively high wage demands despite the poor growth and jobs picture continue to underpin our expectations of sticky, relatively high inflation this year. This comes against a background of both fiscal and monetary policy remaining accommodative.

Inflation expectations are sticky

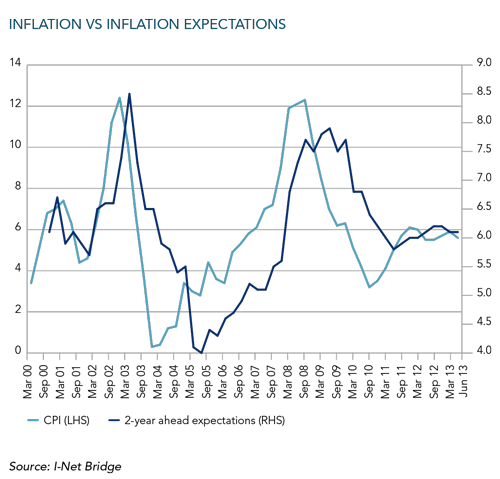

It’s worth examining inflation expectations in a little more depth – partly as the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) focuses on them and appears to be comforted by them being ‘anchored’. Looking at the two-years ahead expectations (as these should be most relevant to the monetary policy timeframe), there are some interesting observations. The first is that expectations have historically been correlated with actual inflation. (Note that the axes on this chart are different to highlight the relationship in trends, but over time, as one might expect, expectations are less volatile than actual inflation.)

Looking in more depth at expectations themselves, it is perhaps notable that, except for a brief dip in 2011 (two quarters at 5.8% – 5.9%), two-years ahead expectations have not been below 6% since the end of 2007. The dip in 2011 came after actual CPI had been below 4% for the second half of 2010 and the first couple of months of 2011, and the fact that expectations could barely get below 6% in the wake of this is a strong indication that survey participants are sceptical of inflation much below the upper end of the range. It is particularly interesting to contrast this with the mid-2000s, when there was a much stronger effect on expectations when actual inflation fell sharply. It is generally thought that the Monetary Policy Committee was more hawkish in those days, and the differing responses in expectations now versus then may be a reflection of this.

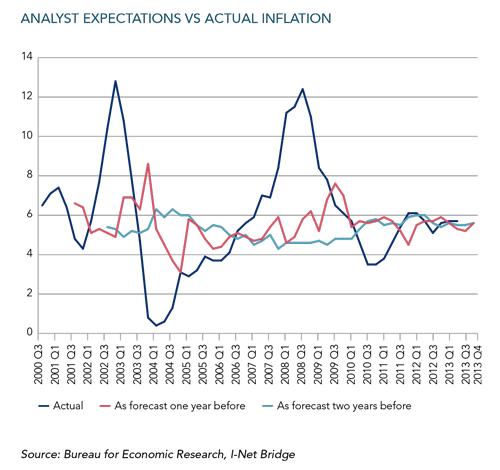

Another angle to consider is how good expectations have been in actually forecasting inflation. For this analysis, I have used the analyst subset of the survey. The chart adjacent is telling. The past couple of years have been broadly in line, partly thanks to stable inflation. However, as can be seen from earlier in the chart, analysts have been particularly bad at forecasting extremes, especially to the upside. This is so despite the fact that the one-year ahead question in particular gives analysts time to incorporate factors such as extreme currency moves (which typically have around a 9 – 10 month lag to affect CPI) into their forecasts. Even worse, the spikes in the forecasts tend to come about a year after the spikes in actual inflation, implying that analysts are very behind the curve in updating their forecasts. In other words, significant rises in inflation are only forecast when they are actually happening. This is one reason that we are sceptical of the current benign consensus on CPI which is largely being explained away by ‘no passthrough’ from the weaker rand and we expect analyst expectations to rise in due course. We expect inflation to be above the target range for most of the next year, if not longer.

What has policy done?

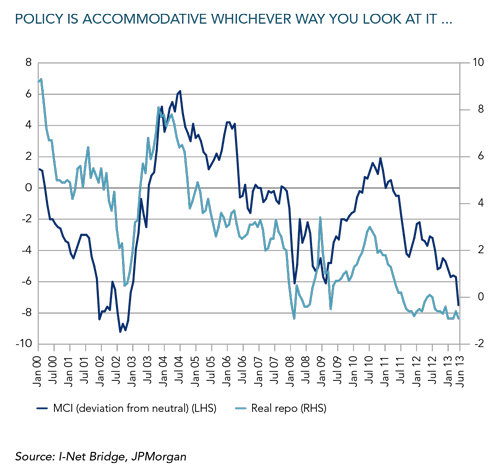

The SARB has left rates unchanged since it last reduced the repo rate (by 50 basis points to 5%) in July last year. By doing so, it has allowed the monetary policy stance to become more accommodative, as inflation has risen and the exchange rate has weakened significantly. The following chart shows two ways of gauging policy. The first method looks at the real SARB policy rate, and the second is a monetary conditions index (MCI). Except for a brief and marginal blip, the real repo rate has been held negative since September 2011. The MCI takes movements in both real interest rates and the real exchange rate into account – a number below zero is accommodative and above zero is tighter policy. It can be seen clearly that the SARB leaving repo unchanged as inflation has risen and the rand has weakened has led to the stance of monetary policy be-coming very accommodative by historical standards over the past couple of years.

The policy stance and growth

Thus, against the background of sticky inflation expectations and upside risks to inflation from the currency and wages, we have monetary policy remaining very accommodative. The obvious reason is that growth remains weak. The problem, really, is that it is not interest rates that are the issue with growth. A combination of weak global demand and labour unrest have been the principal factor affecting local growth data. It’s noteworthy that the Bureau for Economic Research Manufacturing Survey, in the question on constraints on business expansion, polls interest rates as the least important constraint, but the political climate as the most important constraint. These are strong indications as to what is holding back private sector investment in South Africa.

Fiscal policy also remains relatively accommodative, but this is leading to some concerns. South Africa has already had its credit rating downgraded by all the major ratings agencies over the past year as the fiscal stance has stretched some metrics. The recent rise in bond yields will add to government’s interest rate bill, and will further push out the date at which the government debt to GDP ratio is expected to stabilise (this ratio is already at the highest it’s been in a decade and is budgeted to rise further over the next few years). South Africa has also badly lagged its emerging market peers in post-crisis fiscal consolidation, moving from a pre-crisis position of one of the best emerging market fiscal balances to near the bottom of the table now. There is very little room left for fiscal expansion – even before one takes into consideration the composition of such expansion (where the last few years have seen public sector wages rise sharply).

The upshot?

The conclusion of all this, is not a very comforting one. South Africa looks to be headed for a couple of years of relatively low growth – and perhaps one needs to accept that potential growth is not as high as it had been assumed to be a couple of years ago (when forecasts were anchored by the boom years). At the same time, inflationary pressures remain and, given the large current account deficit and less favourable global environment, the rand is likely to remain weak as well. This does imply that there should be some improvement in the current account going forward, but concerns remain that it will still be relatively high for a while. Against this background, policy is in limbo. Monetary policy has probably given all the help it can to growth, but in so doing it also lends negative biases to the currency and inflation (and the SARB has made clear it is loathe to tighten policy against the weak growth backdrop), while fiscal policy is constrained after the significant loosening seen after the global financial crisis. The outcome of all this appears to be an outlook of lacklustre growth, unchanged interest rates, sticky inflation and a weak currency. We don’t see much scope for currency strength against the background we’ve described, but we do think there is the chance that the SARB may have its hand forced on interest rates earlier than it would like (though probably only next year) if our inflation outlook proves correct.

Chantal Valentine joined Coronation as economic and fixed interest strategist in 2003. With more than 20 years’ experience in analysing local and global markets, she plays a critical role in the investment decisionmaking process.

If you require any further information, please contact:

Louise Pelser

T: +27 21 680 2216

M: +27 76 282 3995

E: lpelser@coronation.co.za

Notes to the editor:

Coronation Fund Managers Limited is one of southern Africa’s most successful third-party fund management companies. As a pure fund management business it provides individual and institutional investors with expertise across Developed Markets, Emerging Markets and Africa. Clients include some of the largest retirement funds, medical schemes and multi-manager companies in South Africa, many of the major banking and insurance groups, selected investment advisory businesses, prominent independent financial advisors, high-net worth individuals and direct unit trust accounts. We are 25% staff-owned, have offices in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Durban, Gaborone, Windhoek, London and Dublin and are listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. As at the June 2013 quarter-end, assets under management total R434 billion.

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional