Economic views

Politics take centre stage

“If you want peace, you don’t talk to your friends. You talk to your enemies.” – Archbishop Desmond Tutu

The Quick Take

- 2024 is a political gamechanger and by the time it draws to a close, new international relations may well change the course of the future

- The USA’s election is the one that will have the most significant impact – especially with respect to prevailing conflicts

- With marginally lower inflation, we expect policy rates to ease globally

- SA is not out of the woods, but there is some hope that the new government will implement a reform agenda

“Globally, more voters than ever in history will head to the polls, as at least 64 countries (plus the European Union) – representing a combined population of about 49% of the people in the world – are meant to hold national elections, the results of which, for many, will prove consequential for years to come.” Time Magazine, December 2023

We have passed the year’s halfway mark, and a significant number of scheduled elections have already been held, as well as some that weren’t scheduled. Several have had materially unexpected results. In some cases, a free and fair democratic process was observed and accepted; in some, it was not so smooth. The results will, in all cases, have a meaningful influence on political and economic outcomes in the respective countries and associations. And the biggest national election is yet to come, as the Republicans and Democrats face off in the USA.

A JUMP TO THE LEFT… OR A SHIFT TO THE RIGHT?

The year started with presidential and parliamentary elections in Taiwan. This election was important because of Taiwan’s contested relationship with China, and growing tensions in the Taiwan Strait between the two, with Taiwan backed by mighty allies. While the Democratic People’s Party won the election and presidency, it lost its majority. China’s response to the pro-independence president was negative, and there is no sign of abatement.

The European Union Parliamentary elections in June saw French nationals vote strongly in favour of right-wing party National Rally (RN) led by Marine le Pen. This outcome prompted French President Emmanuel Macron to announce snap parliamentary elections at home. Run in two rounds, a week apart, the initial round went to RN, but was followed by a massive swing to the left in the second round, with a surge in support for the left-wing coalition New Popular Front (NPF). This leaves France with a hung parliament, a president with no mandate, and even more disordered domestic politics than before.

In the UK, the Conservatives lost to Labour, with former Prime Minister Sunak’s early election yielding a very weak outcome for the incumbent party. A quiet transition to what is expected to be a largely technocratic Labour government, focusing on service delivery within the UK’s very constrained fiscal position, has already taken place.

There were surprises in emerging markets too. Despite its leader’s popularity, Indian Prime Minister Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party lost its majority. In Mexico, former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s (aka AMLO) centre-left, progressive National Regeneration Movement (Morena) party swept to a super majority, enabling his successor, President Claudia Sheinbaum to make changes to both the Constitution and the judiciary.

In South Africa (SA), the ruling African National Congress (ANC) also lost its majority, conceding a free and fair election. The new ruling coalition faces historic and ideological hurdles, but arguably shares several common causes. This could meaningfully improve the growth outlook if acted on.

The recent assassination attempt on US presidential candidate Donald Trump has boosted his popularity in the polls. While many uncertainties related to the US election persist, the economic and political policy choices of a second Trump administration could see dramatic changes to already-fragile domestic fiscal as well as geopolitical balances.

Running in the background, but certainly likely to influence the shifting political tectonics are the ongoing wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Already, Russia’s Putin has signalled an offramp to the conflict in Ukraine if Trump wins the US presidential election; while the risk of escalation in the Middle East threatens stability beyond just the region itself, as the war has started to become a political divider globally.

The economic impact of political change takes time to be felt, as assets reprice and policies adjust. Given the outcomes to date, these changes are more likely to be disruptive of the current status quo than providing continuity. The US election is the biggest uncertainty, but Mexico, India, SA, the UK, and France all have shifting policy mandates.

GLOBAL ECONOMIC UPDATE

The global economy has once again proven to be more resilient than was anticipated early in the year. Specifically, the US continued to enjoy tight labour markets and solid domestic demand. Real GDP growth is expected to be only marginally slower in 2024 than in 2023, at 2.3% from 2.5%. Sticky inflation – despite slowing food prices and weak goods inflation – has kept the Federal Reserve Board’s policy rate on hold. However, more recently, some weaker activity indicators and better evidence of moderating inflation have reignited expectations of some easing before year-end.

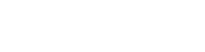

In Europe, the growth trajectory has been a little different. Very weak growth in the first quarter has picked up as the cost-of-living constraints combined with the dual impact of restrictive monetary policy and fiscal consolidation in some countries has eased. GDP growth is expected to accelerate to 0.8% in 2024, from 0.6% in 2023. While inflation’s retreat has been uneven, the European Central Bank (also later than initially expected) cut policy rates by 25 basis points (bps), taking the deposit rate to 3.75% in June. Japan has surprised expectations with mounting evidence of a sustainable recovery in inflation, as price pressures have pushed up wages. Figure 1 plots regional growth and forecasts.

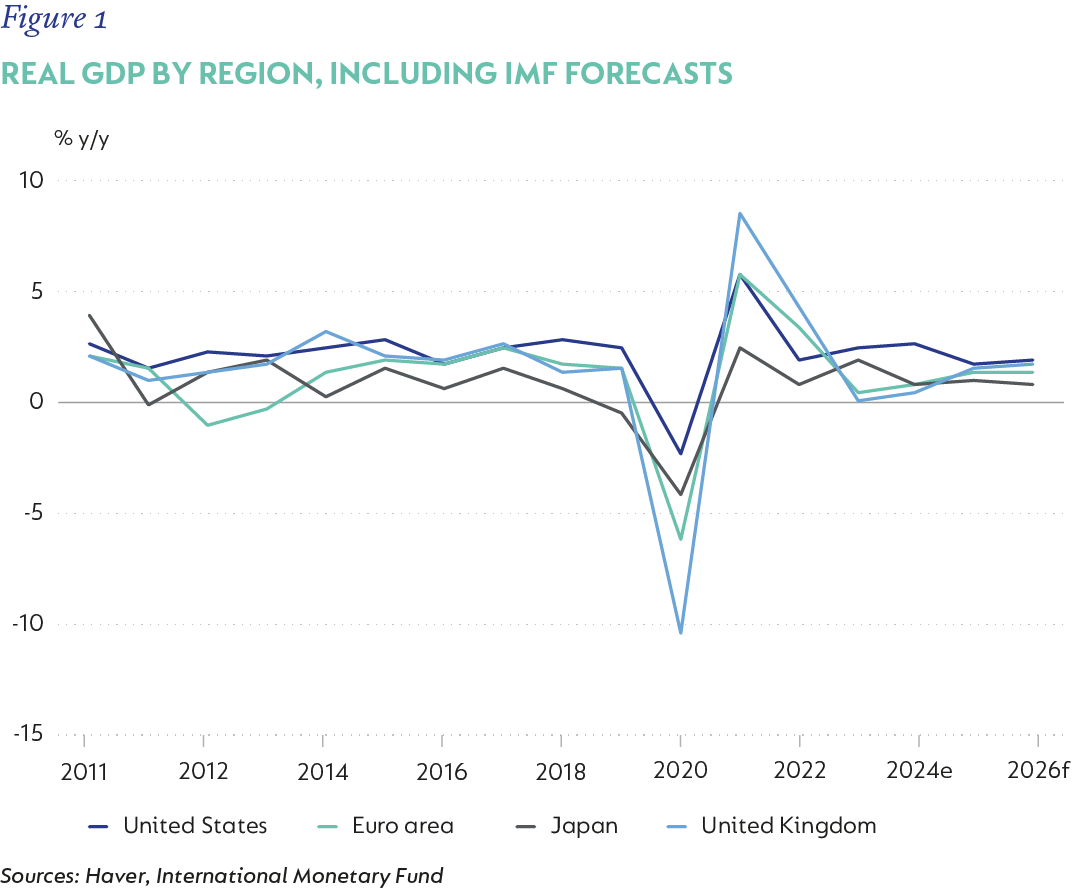

Taken together, a more benign narrative around developed market economic growth is emerging. With the expansion broadening (with some signs of a sharper slowing in some sectors), inflation is expected to slow a little more (but remain above target) and a modest easing cycle is anticipated in late 2024 into 2025 (Figure 2).

Emerging markets have seen an uneven growth expansion, but a much more pronounced improvement in inflation (driven by an easing in food and fuel prices) has provided the various central banks with greater scope to ease monetary policy. Nonetheless, high developed market policy rates are not a friendly environment for emerging market assets, and a strong US dollar has kept emerging economy exchange rates on the back foot. This has been exacerbated by China’s weak domestic economy, with its real estate sector under immense pressure, and growth being largely kept afloat by strong export performance. Price disinflation – and at times deflation – has limited policy options and hampered economic consolidation in the world’s second-largest economy.

CLOSER TO HOME, THE ELECTION DOESN’T FIX THE ECONOMY – YET

The ANC lost its 30-year majority in the May 29 election. In the following two weeks, it drew the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), along with a range of smaller parties into a fractious alliance under the umbrella of a Government of National Unity (GNU). The significance of achieving this arrangement, when there was a potentially ‘easier’ alliance with the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and other smaller parties, shouldn’t be underestimated.

President Ramaphosa appointed a cabinet that includes seven other parties, albeit retaining a strong (71%) ANC presence (including the president and deputy and all deputy ministers), with the DA holding 15.6% ministerial positions and the remaining parties at 13.4%. Looking ahead, the ability of the two larger parties, the ANC and DA, to move beyond historic political confrontation, and ideological and economic differences – especially when the ANC itself is now even more visibly divided after the election – remains to be seen.

Certainly, there is significant common ground on which to build. Many ministers in the economic cluster value private participation and partnership with government and have committed to pursuing policies in line with this. Seeking to improve service delivery, IFP leader and Minister of Cooperative Development and Traditional Affairs has called for municipalities to improve critical service delivery, or have these responsibilities removed and face liquidation. Minister of Transport, Barbara Creecy, has prioritised the stabilisation of the sector, and the creation of a private sector participation unit to boost its investment in SA’s transport infrastructure and operations. National Treasury’s determined efforts to consolidate spending and commit to a fiscal anchor should find greater support in a more representative cabinet. And, although SA was not keen on a bigger cabinet, a positive outcome is that ministerial accountability should also improve.

Critically, Operation Vulindlela’s prioritised interventions to fast-track economic reform provide a roadmap for the reference of new ministers, with a high level of political support. There are also a number of key legislative decisions – including revised White Papers on transport and logistics, the Water Services Act, and the National Water Infrastructure Agency Bill – which are already in motion for 2024, paving the way for constructive interaction by the coalition in the near term.

That said, there is clearly a part of the ANC that is more closely aligned to the EFF or even the uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP), which has been spun out of the party over time. This has the potential to be a powerful grouping within the government.

SA ECONOMIC OUTLOOK.

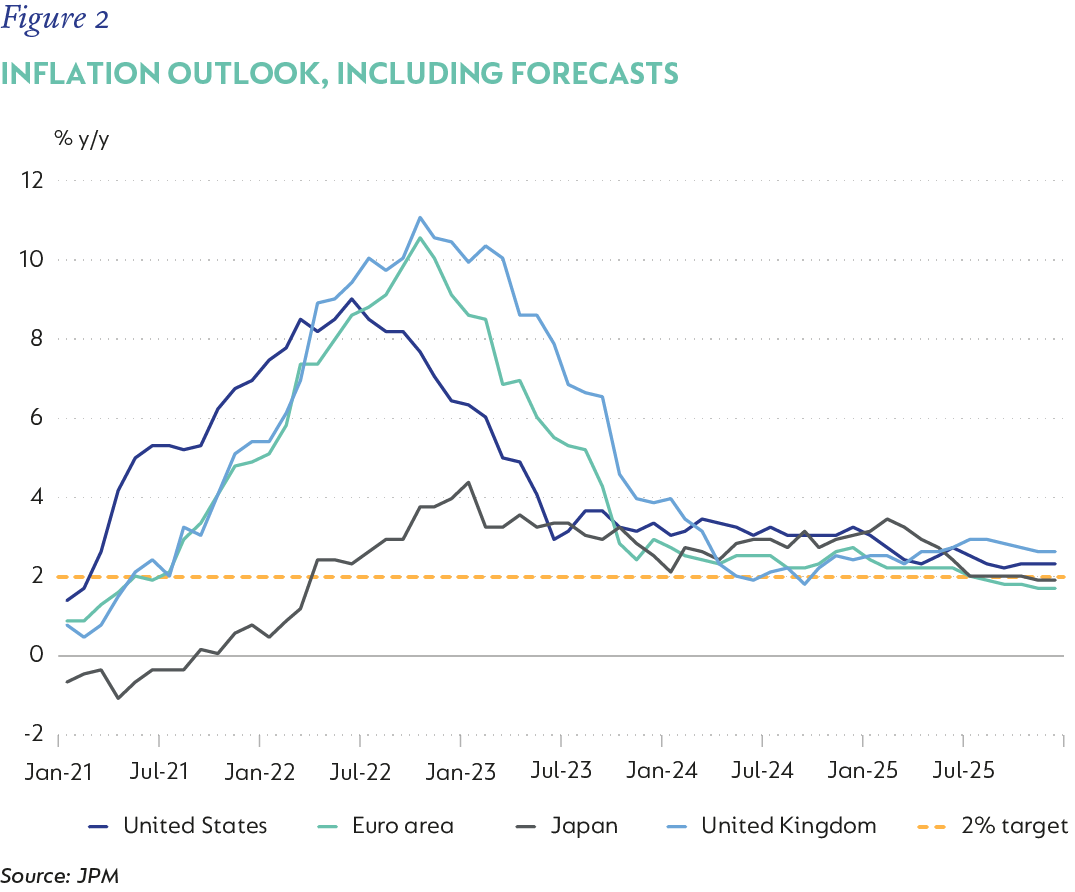

GDP growth started the year on a back foot, following a weak end to 2023. Figure 3 shows that, on a sequential basis, real GDP contracted 0.1% quarter-on-quarter in the first quarter of this year (Q1-24) and eked out poor gains of just 0.6% year-on-year (y/y). Data for the second quarter has been patchy, with little real evidence of the loadshedding relief in the numbers, although we see an upside of between 0.5 and 0.8 percentage points of GDP, should loadshedding be contained to levels 1-2 in the second half of this year into 2025.

A significant part of the growth challenge is that few of SA’s economic headwinds are cyclical. GDP growth peaked in 2006 and has been slowing on a trend basis since the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis. The drivers of the deceleration include:

- a deterioration in the business climate alongside rising political and social risks;

- the impact of negative supply shocks, including the sectoral deterioration in electricity, transport, and water;

- labour market inefficiencies;

- the effects of State Capture on productivity;

- wasteful spending, misgovernment, and corruption in the allocation of resources; and

- the impact of the weakening fiscal position on borrowing costs and the crowding out of private investment, amongst others.

None of these issues were short in the making, and all will take time to resolve. We are encouraged by the new configuration of government, especially in instances where ministerial heft can be brought to critical issues of reform already presented by Operation Vulindlela (such as energy and transport, skilled visas, and communications), but a full commitment to critical projects will take time.

As such, the near-term drivers of growth can only really come from an improvement in current headwinds and better sentiment, but these improvements are likely to be marginal.

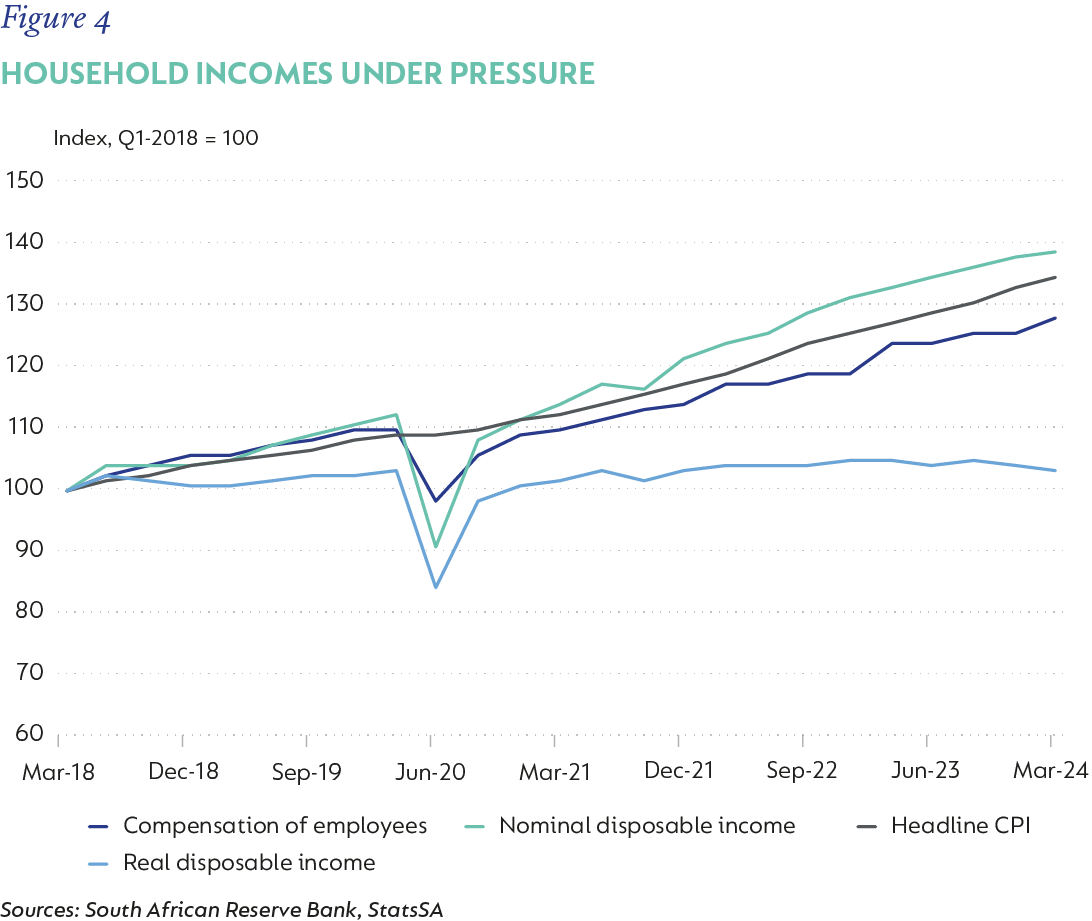

The outlook for domestic consumers has started to improve (Figure 4), supported by lower inflation, real wage gains and the prospect of lower interest rates. Consumption accounts for 67% of GDP (and about 61% of government revenues), and household spending has been deeply bruised by high inflation, the increase in interest rates, and debt service costs; and, more recently, fiscal pressure, which provided no relief from bracket creep this year.[1]

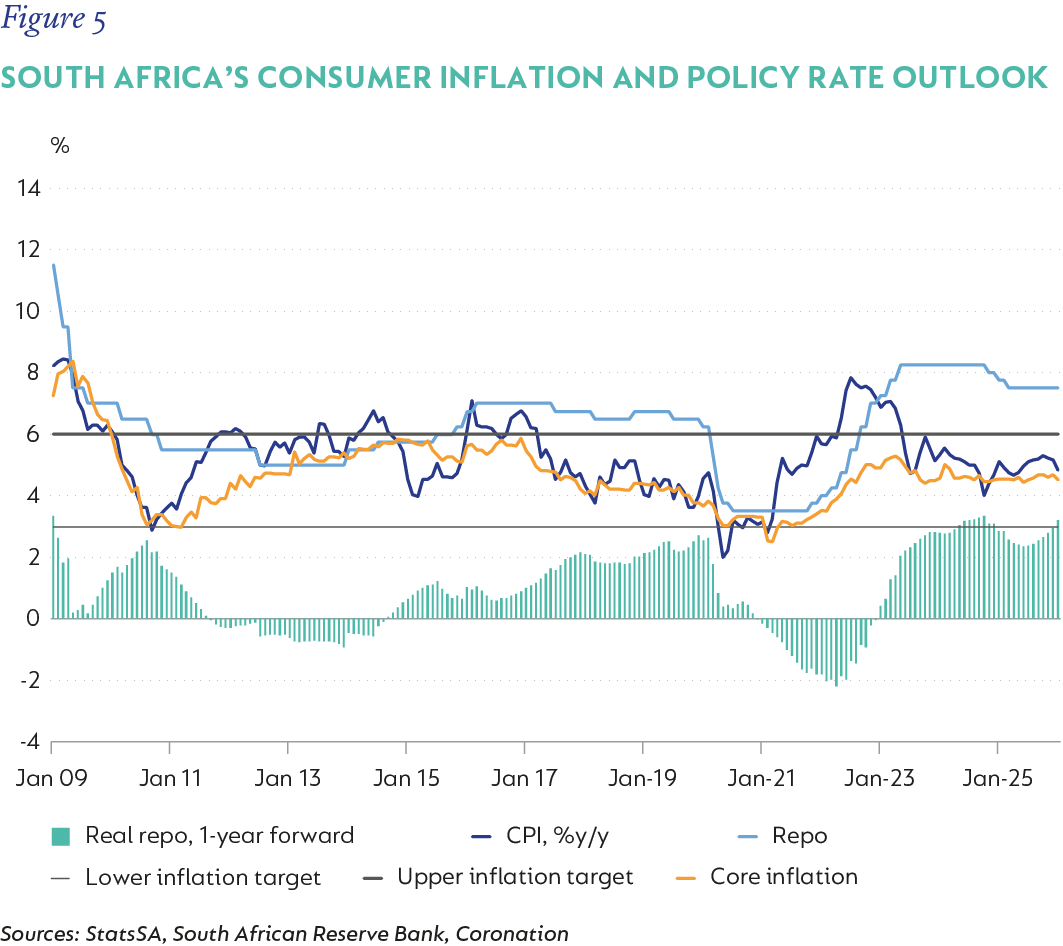

We expect these constraints to start easing, as inflation is set to slow to about 4% y/y in October, driven by lower pump prices for fuel, easing food prices, and some knock-on from a stronger currency. We see consumer inflation averaging 5% this year and next, with core inflation steady at 4.6%, an anticipated reduction in interest rates, and a modest acceleration in credit utilisation should help support spending (Figure 5).

With some uplift from consumer spending, and a marginal easing in energy and logistics constraints amidst a looser global policy environment, we see scope for growth to accelerate in the second half of 2024 to bring annual GDP to 1.1% in 2024, 1.6% in 2025, and 1.8% in 2026.

We see limited room for a strong response to changing conditions from private capital expenditure, although a more enabling regulatory and political environment could present significant upside.

The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has been cautious about the outlook for inflation, and, through most of the past year, has assessed the risk to its forecasts as being to the ‘upside’. Some of these risks – including currency weakness and the threat of higher food prices – have receded, and we expect the SARB to start cutting the policy rate in the fourth quarter of this year, with some risk[1] of an earlier start (end-Q3-24) to a 75bps easing cycle. We see the ‘terminal’ repo rate at 7.5%, limited by the weak fiscal position and, possibly, an official lowering of the inflation target in 2025.

National Treasury has done well in containing spending in the fiscal year 2023/2024, delivering a primary fiscal surplus of 0.3% of GDP, excluding allocations to Eskom. This certainly improves the current year’s starting position. Looking ahead, however, decisions about large allocations (such as the long-term future of the Social Relief of Distress grant and funding of national health insurance, have yet to be made. Greater efficiency in fiscal allocations is possible under the new administration, but we believe that it is too soon to embed greater restraint in the numbers until there are clearer indications of the political dynamics within the new government.

A weak new dawn?

It is said that a day is a long time in politics, and now, perhaps, more than ever, this is true in SA. Much has changed in a short period of time, but much is also still the same. The ANC, still responsible for many of the inefficiencies and administrative failures of government, retains a heavy majority of ministerial positions (including deputies) and roughly 73% of the Budget allocation. It is not clear whether or not the new administration is reorientated enough to create a growth-enabling environment that can support stronger, more inclusive growth. There is also now clearer internal opposition to the coalition, which will need careful navigation. The political arrangements in the provinces have yet to be tested.

But there is a case to be made for cautious optimism, given the initial success in agreeing a coalition, and early indications of a renewed focus on a common reform agenda.

[1] Inflation pushing taxpayers into higher tax brackets without income increases

[2] While desirable, early easing in the policy rate carries several potential risks, such as an uptick in inflation, currency weakness and negative market sentiment, among others

Insights Disclaimer

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal