Economic views

The balance of things

- The economic benefits of targeting lower inflation are clear – the timing isn’t

The Quick Take

- The cost-of-living crisis had a materially negative impact on election outcomes for incumbent governments globally in 2024

- SA’s inflation target is dated; it’s too high relative to peers, potentially undermining the mandate of the central bank

- However, adjusting the target requires careful consideration of broader economic objectives and potential implications.

- Specifically, the timing and timeline for changes need to be well flagged and in tune with the country’s economic and fiscal challenges

“4.5% is not an optimal target, it is a logical and balanced recognition of a target we should have reformed two decades ago.”

- Lesetja Kganyago, Governor of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), September 2021

People really hate inflation. In 2024, roughly two billion eligible voters in more than 70 countries went to the polls in the largest election year in history. Taking stock of the outcomes of these elections distils a very clear message: 2024 was the year in which incumbents lost power, with the cost-of-living crisis an overwhelming factor in voter discontent. Rob Ford, professor of political science at the University of Manchester, said inflation has been a major driver of “the greatest wave of anti-incumbent voting ever seen.”

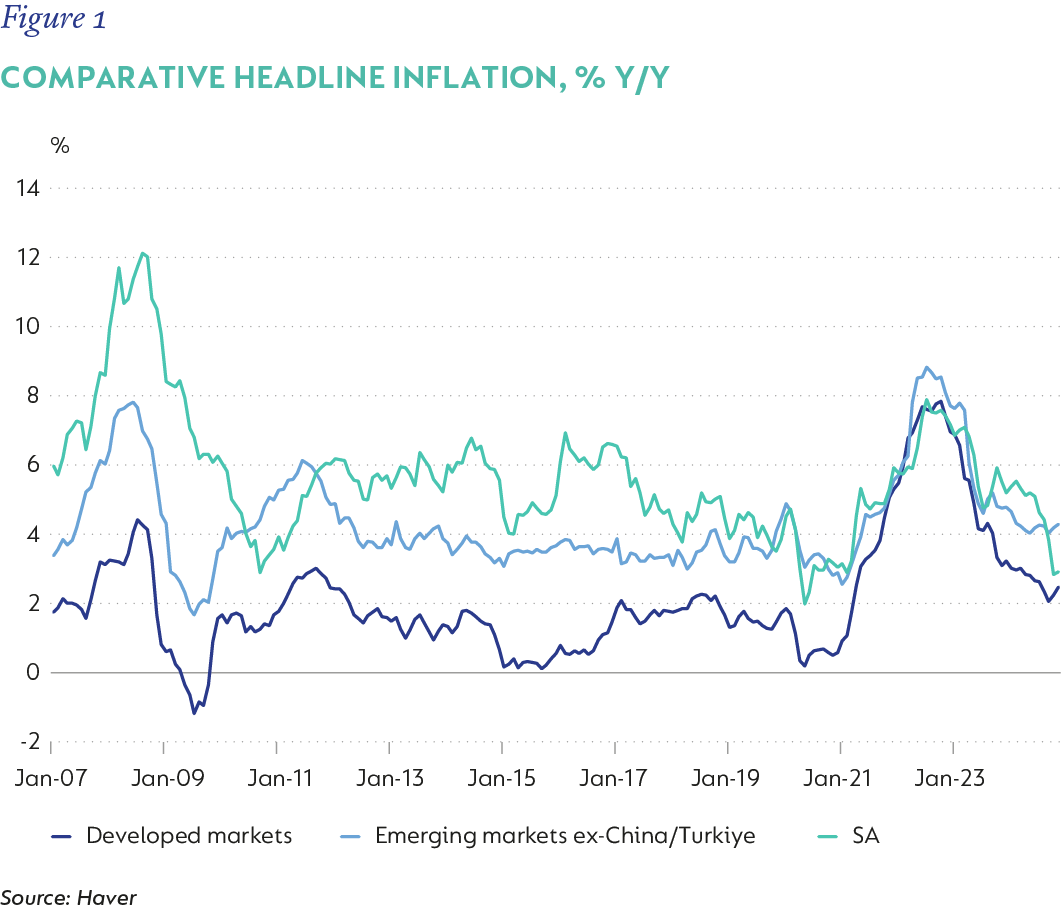

Figure 1 shows that, while South Africa (SA) was not immune to the post-Covid inflation surge, we got off comparatively lightly. Headline inflation accelerated from a nadir of 2.8% in February 2021 to a peak rate of 7.8% in July 2022. By the end of 2024, it had slowed below the lower limit of the SARB’s target band of 3%. This compares to a developed market average of 5.6% (and an aggregated peak of 8.4%) and an emerging market average (ex-Türkiye and China) of 6.2% (8.8% at peak). Our economy’s more muted inflationary response, in part, reflects less extreme pressure on key components, like food and fuel, than was observed elsewhere. This is especially noteworthy in the wake of the massive Covid-related fiscal and monetary stimulus and the Russian invasion of Ukraine – as well as a weak underlying economy; but it is also a well-deserved reflection of the SARB’s commitment to its inflation target over a long period, supported by its independence and hard-won credibility.

THE CLEAR BENEFITS OF LOW INFLATION

Economies work best when there is price stability. Low, stable, and predictable inflation helps people plan their saving, spending and investment goals. It helps avoid the inefficiency cost of nominal rigidities (where prices don’t adjust to prevailing conditions), protects purchasing power, especially that of the economically vulnerable, and the value of savings. Over time, it lowers the cost of borrowing, which supports sustainably higher growth and employment. As we have seen, failing to contain inflation has very real consequences.

SA officially adopted inflation targeting in 2000, following a period of informal or ‘eclectic’ monetary policies. Officially, the primary mandate of the SARB is to protect the value of the currency in the interest of balanced and sustainable economic growth. It delivers on this mandate by targeting inflation, which sets a measurable benchmark against which it is accountable. The SARB’s independence in doing so is enshrined in the Constitution, which also states in section 224 that the SARB must perform its functions ‘without fear, favour, or prejudice’. These are important foundational principles that must be upheld to ensure a successful policy outcome over time. In addition to this, the SARB has a statutory mandate to enhance and protect financial stability in SA.

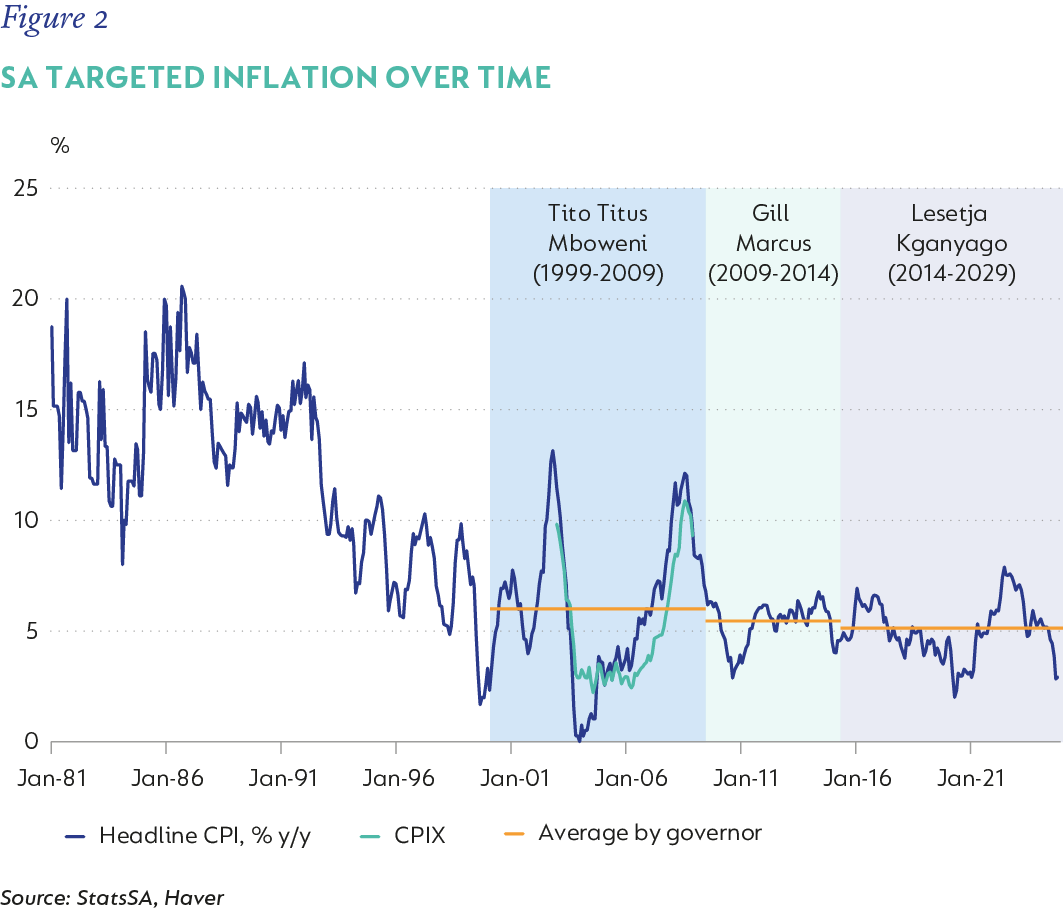

The initial inflation target was set by National Treasury, in consultation with the SARB, in the year 2000, at an average rate of 3% to 6% of CPI ex-interest rates on mortgages (CPIX) for three years. At the time, annual average inflation was 7.3% and the intention was to narrow the band to between 3% and 5% in 2004, and then contain it between 2% and 4% thereafter. However, the currency crisis of 2000/2001 delayed this downshift, which was subsequently abandoned.

In 2008, then-Finance Minister Trevor Manuel announced a change in the target measure to headline CPI, citing an alignment with global trends. In 2010, Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, in a letter to then-SARB Governor Gill Marcus, reiterated the retention of the inflation target of headline CPI in a range of 3% to 6%. No other formal changes have since been announced, although Governor Lesetja Kganyago, since his first term, has actively pursued a target closer to the mid-point of the range at 4.5% which has successfully lowered inflation over time.

INFLATION TARGETING REVIEW

Inflation targeting in SA has had mixed success when measured since inception. In the early years, inflation was volatile, buffeted by a series of largely exogenous shocks that saw the currency whipsaw and prices respond. Price indexing (especially of wages, but also of other services) was initially sticky, and, while these have moderated, they still play a role in creating price inertia in some components of the inflation basket. Following the Global Financial Crisis, volatility eased, but inflation settled close to the upper bound of the target range for most of the time. It wasn’t until more recent concerted efforts to communicate – and deliver – on inflation closer to the mid-point that overall performance improved (Figure 2).

A formal study[1], sponsored jointly by National Treasury and the SARB, provides a comprehensive review of monetary policy between 2007 and 2021, and commends the SARB on its successful communication and well-judged policy actions over the period. However, the study found – on balance – the current target to be ‘undemanding’ and ‘high’ by peer comparison. Specifically, SA’s formal target is set both higher and with a wider range than most of its peers. This creates several challenges:

- While SA has managed to achieve its mandate most of the time (unlike peers), the higher level of inflation has undermined competitiveness, placed additional pressure on the poor and, ultimately, been negative for the relative value of the currency – which is the SARB’s mandate to protect.

- Although many emerging market peers have consistently missed their targets, average realised inflation has been lower than SA’s since inception.

- High levels of indexation have reinforced SA’s high inflation, including wage setting (notably the State) and other areas of fiscal policy, such as social support and long-term market expectations of inflation.

- All of SA’s peers have adjusted their targets (lower) over time, widening the average gap between these and SA’s unchanged target range (although SA’s successful targeting matched against peer misses has actually narrowed this differential more recently).

The review also found that the 3 percentage point (ppt) range is too wide, making it too open to interpretation and unable to offer an effective anchor. The targeted midpoint, an improvement, is also not low enough for price stability and as such has reduced the potential benefits of the mandate. A lower target, recommended at 3%, would strengthen the SARB’s credibility through limited sacrifice rates and reduced vulnerability to shocks.

With these findings in hand, the SARB has widely promoted the advantages of a lower inflation target. Its modelling[2] of a shift to a 3%-point target with a narrow tolerance showed broadly beneficial outcomes at a limited cost. Specifically, modelling the impact of a five-year transition to a 3% inflation target on real GDP growth shows an initial sacrifice[3] of 0.3ppt. This would be attributed to an increase in real rates due to falling inflation expectations and a strengthening currency, not through higher nominal interest rates. However, this sacrifice is more than compensated for by higher growth in subsequent periods.

NUANCING THE NARRATIVE

In theory, these goals are achievable and should deliver deeply positive economic outcomes. Practically, the path to success may be more challenging. Modelling the prevailing real repo rate required to sustain inflation at 3% is difficult because there is limited data at this level. However, suggesting that the economic cost is both limited and offset by longer-term gains may also be optimistic.

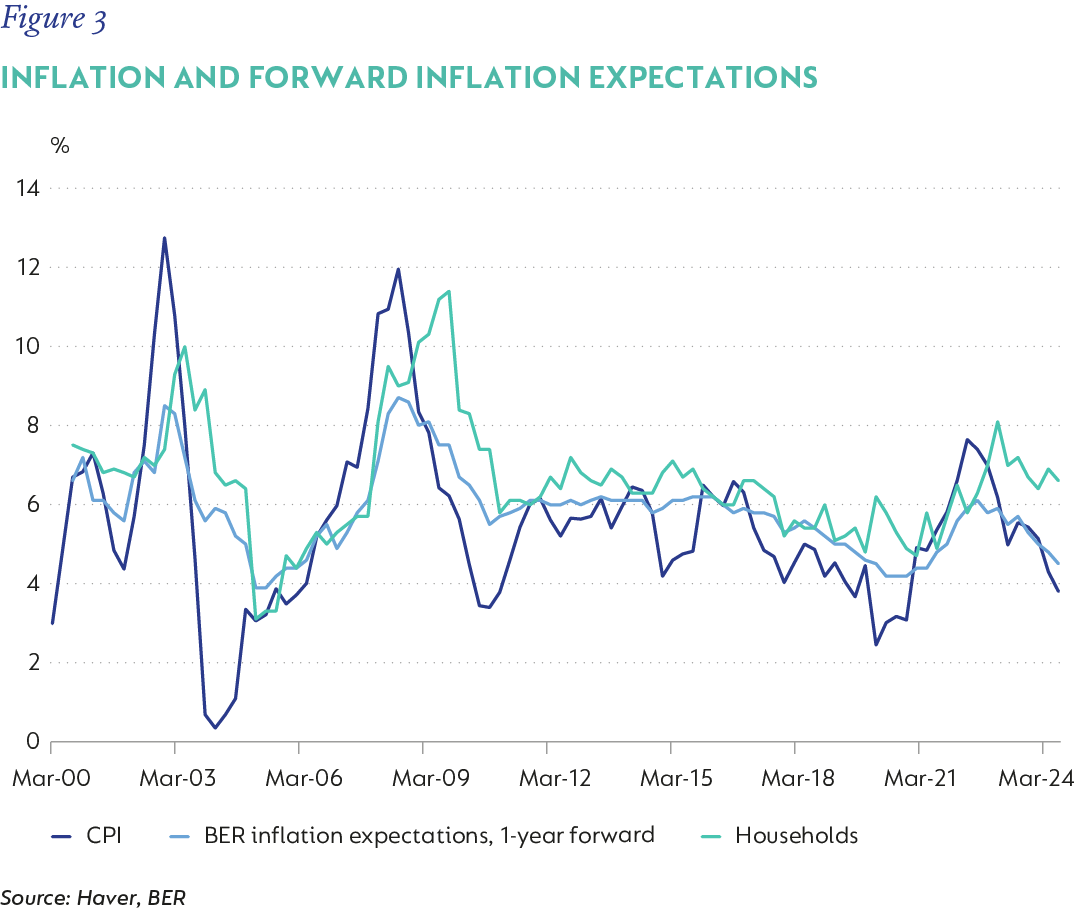

Our own modelling, which excludes the early period of high inflation volatility (i.e., using a period in which inflation has largely been successfully held within the target band), suggests that a real repo rate of between 2.75% and 3.15% is needed. Critically, but in line with the SARB’s modelling, including forward-looking inflation expectations[4] (Figure 3), lowers the required real repo rate by about 50 basis points (below the SARB’s current neutral estimate) to 2%-2.5%. Over time, this translates into a materially lower nominal neutral rate of about 6%.

Modelling by Standard Bank[5] suggests that, depending on how swiftly inflation expectations become anchored at lower levels, real GDP could be between 0.7% and 2.6% over four years of implementing a 3% inflation target.

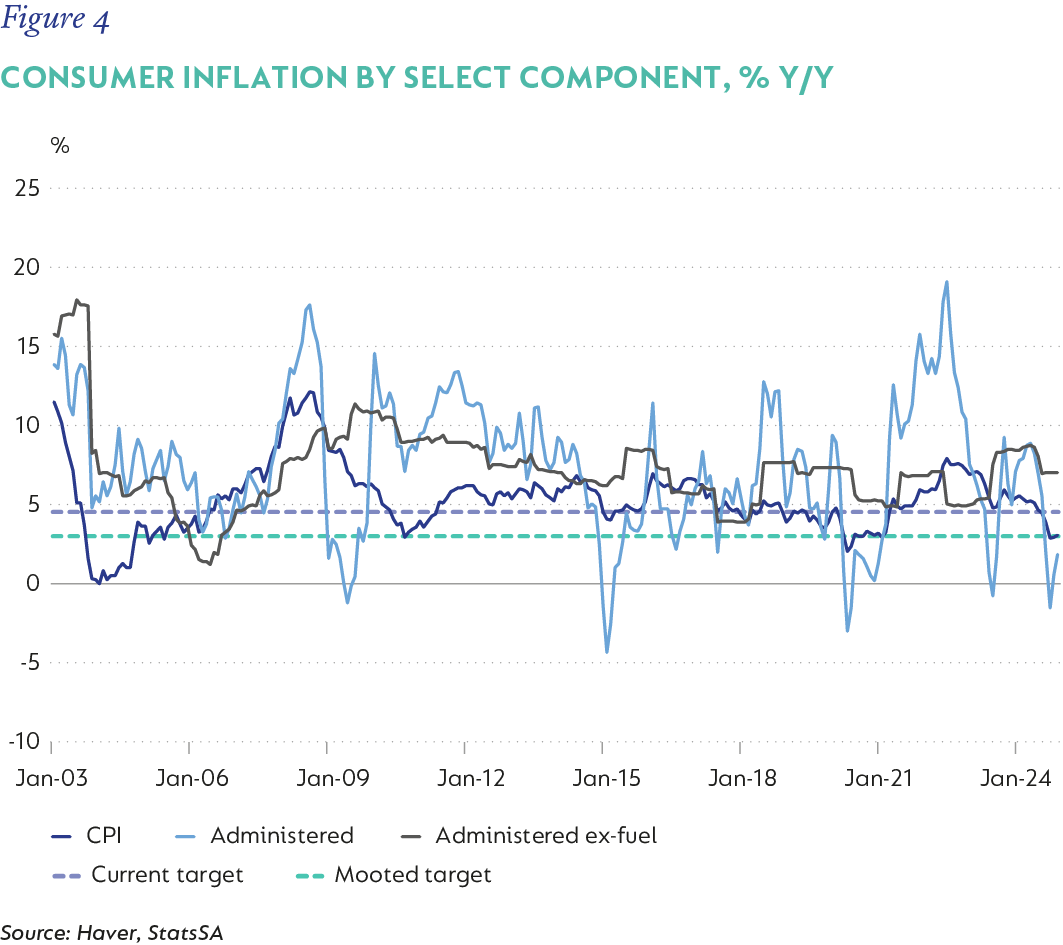

From a ‘bottom-up’ perspective there are practical challenges to achieving lower inflation. While food and fuel account for much of the volatility in inflation, services - which include administered prices - play a significant role in shaping overall inflation outcomes. Services make up a substantial 51.3% of the CPI basket, with administered prices together contributing just under 32%, and the two rental measures account for a little over 32% of the remainder. Currently, administered prices excluding fuel are driving inflation at 7.0% year on year (y/y) as at December 2024, while total administered price inflation low, anchored by fuel deflation, it is now rising (Figure 4). The uncertainty related to future pricing of utilities – notably water and electricity – suggests greater upside than downside. Weak rental inflation is also helping keep administered prices low, and while we don’t expect rental inflation to return to its 5% trend, but we do expect it to continue to recover gently from here.

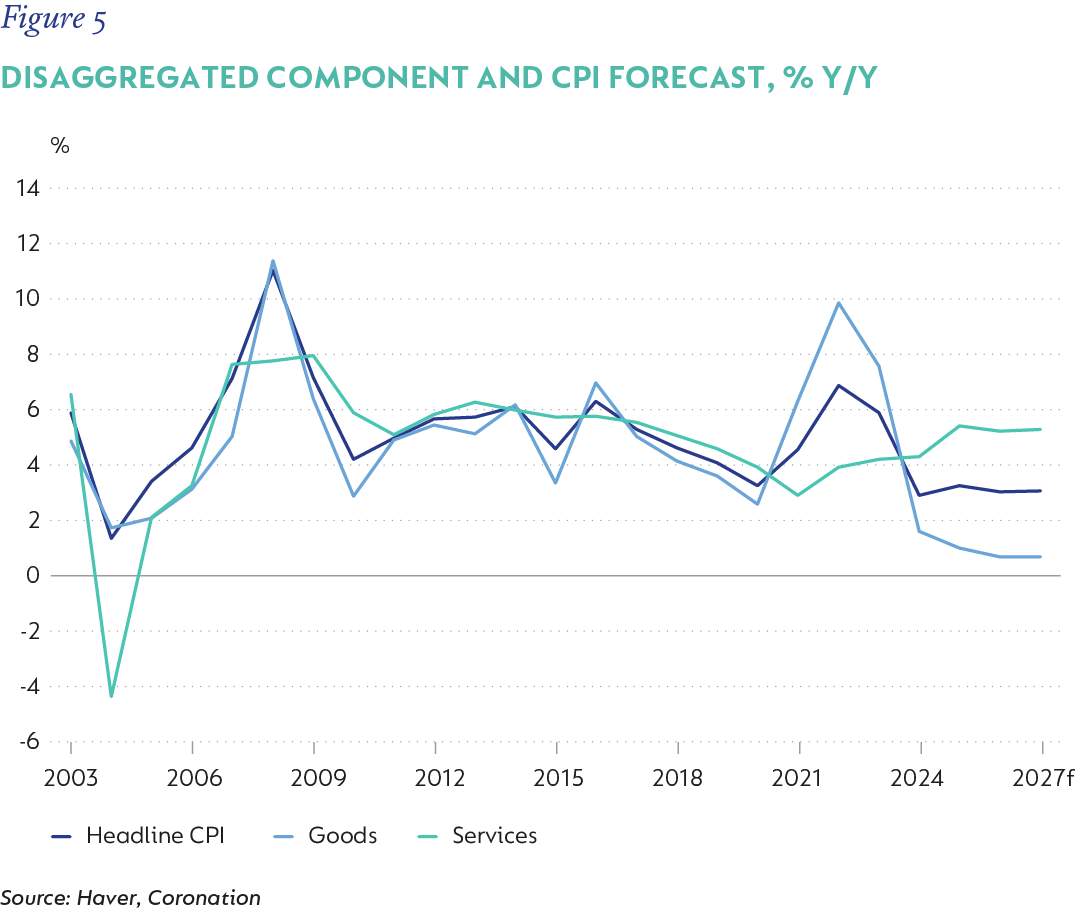

Simple modelling suggests that given expectations for broader services and administered prices – all else being equal – goods inflation would need to trend below 1% to achieve a 3% target (Figure 5). The reweighting of the basket, which will be published early this year, may have an impact on these measurements but is unlikely to materially affect this outcome.

FINANCIAL STABILITY CONSIDERATIONS

From a broader economic perspective, monetary policy isn’t the only game in town, although a lot has been asked of central banks since the Global Financial Crisis! SA’s fiscal position remains vulnerable. National Treasury has fought hard to consolidate expenditure and has committed to continue to moderate core spending over time. This implies a smaller government, with lower expenditure relative to GDP and will remain a headwind to growth for a considerable period. In the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (October 2024) National Treasury reiterated its commitment to fiscal sustainability through a rising primary surplus and long-term moderation in the debt ratio. It aims to formalise this process through a legislated fiscal anchor in time.

Despite some successes, fiscal challenges remain considerable, as several key issues remain unresolved. These include the cost of the coming years’ wage bill; the future of the Social Relief of Distress Grant; rising debt at the local level, which affects Eskom and the Water Boards; funding for State-owned entities; and, possibly, additional allocations to health and education budgets, which have been cut to the detriment of critical programmes. These fiscal pressures are exacerbated by still-weak underlying growth.

Achieving National Treasury’s fiscal ambitions is going to be politically and economically difficult. Weak growth outcomes will undermine these efforts and could still see the ratio of debt continue to rise. The economic risk associated with an unsustainable fiscal trajectory outweighs the considerably more contained risk (in SA’s case) of inflation that runs higher than peers, especially in the near term. Put differently, achieving an economic environment that eases fiscal tension, facilitates consolidation, and lowers risk premia, while keeping inflation low, would make the SARB’s job of achieving a lower inflation target considerably easier in the longer term. Attempting fiscal consolidation alongside a lower inflation target may require even greater austerity to achieve debt stabilisation targets. The best outcome – ‘balanced and sustainable growth’ in the longer term – may need a fine-tuning of monetary and fiscal coordination in the near term.

The IMF has recently commended the SARB on its high level of transparency in its Central Bank Transparency Code Review[6], noting the SARB’s independence as fundamental to its credibility and success. But mandate and instrument independence should not make the SARB too distant from political realities. The Review also noted that “recent discussions about revising the inflation target have led to uncertainty among some external stakeholders regarding the respective roles of the SARB and National Treasury in this process. Hence, more clarity is advised with respect to the review of the SARB’s monetary policy framework and the setting of the inflation target by the Treasury in consultation with the SARB.”

BOTTOM LINE

A revision of South Africa’s inflation target is overdue and may be undermining the SARB’s ability to fulfil its core mandate. Anchoring inflation at a lower level, possibly with a narrower tolerance band, intuitively offers tangible, broad-based economic benefits. However, running in parallel with the very necessary and increasingly challenging fiscal consolidation currently underway, creates a combined headwind to growth that may be considerably greater than initial modelling suggests.

Clear and transparent communication from the National Treasury, in collaboration with the SARB, is essential. This should include a well-defined timeline and an extended implementation runway, enabling the SARB to manage expectations lower over time, while also giving it greater flexibility to keep inflation within target acknowledging broader economic objectives. This is a challenging time at which to be deliberating this policy change given the complexity of the process and its far-reaching economic implications. It needs to be considered and communicated with care.

[1] Honohan and Orphanides, “Monetary policy in South Africa, 2007 – 2021”, TIED-SA Working Paper #208, March 2022

[2] Monetary Policy Review, Box 1: “Do Fiscal and Monetary Complementaries matter?”, South African Reserve Bank, April 2024

[3] The ‘sacrifice’ ratio measures the cost of reducing inflation in terms of foregone GDP

[4] Using the Bureau for Economic Research 1-year ahead forecasts

[5] Moolman, E “SA Macro and Fixed Income Outlook 2025: Promising progress”, Standard Bank, January 2025

[6] South Africa: Central Bank Transparency Review, IMF Country Report, December 2024

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal