Investment views

Bond Outlook

The Quick Take

- Nearly half the global population will have gone to the polls this year, causing increased market volatility and risk aversion

- SA bonds have benefited from a reduction in risk premium following the formation of the GNU

- SA’s economic trajectory has not shifted, and fiscal deterioration remains a key risk

- SAGBs now embed a lower risk premium and trade closer to fair value

This year, an unprecedented number of elections are being held globally, with almost four billion people from c.60 nations heading towards the polls. In the last quarter, major emerging and developed markets saw some surprise results. India’s Bhartiya Janata Party lost its majority; Mexico’s Movimiento Regeneración Nacional won a constitutional majority; the UK elected its first new governing party in 14 years; and chaos erupted in France, caused by its call of a snap election – with the Republic narrowly missing far-right dominance due to a rushed left coalition. Election anxiety reached fever pitch in South Africa (SA) during the second quarter of 2024, with the African National Congress (ANC) losing its majority, forcing it into a government of national unity (GNU) with opposition parties. US election unease has started ahead of its November ballot, and one can expect more volatility as we approach the event.

SA fixed-income markets were on a roller coaster ride over the last quarter. The yield on the 10-year bond traded well over 12% into the elections before crashing down to sub 11% by the end of the second quarter of 2024 (Q2-24) as the details of the GNU emerged, calming investor angst. The FTSE/JSE All Bond Index (ALBI) was up 7.5% over the quarter, bringing its 12-month return to 13.7%. This is well ahead of cash, with a quarter-to-date (qtd) return of 2% and a one-year return of 8.3%; and inflation-linked bonds, with a qtd return of 2.4% and a one-year return of 9.1%. Bond performance was driven by the outperformance of bonds in the belly of the curve (less than 12-year maturity). The rand gained c.4% against the US dollar, which also put the ALBI’s return ahead of global bonds (-3.6% in rands qtd and -2.6% over one year).

TOGETHER WE STAND; DIVIDED WE FALL?

The ANC’s loss of its majority has ushered in a new era of coalition politics under the GNU. Hopes of a reduced cabinet (and lower wage bill) were dashed, with several dual deputy minister roles being introduced to appease members of the 11-party GNU. Key ministries within the cabinet still remain under the control of the ANC, with many underperforming ministers returning to their roles. The ANC still controls 22 out of 34 ministries and the Democratic Alliance (DA) controls six out of the 34, while the ANC has 31 out of 38 deputy ministers and the DA has five out of the 38. Overall policy direction will still be shaped by the ANC in many of the key areas of economic development. More importantly, the implementation of said policy will be at the behest of the ANC with limited influence from opposition parties. This opens up the risk of a continuation of the glacial pace of reform that we have become accustomed to. On the positive side, with the introduction of opposition parties into the various ministries, there should be increased scrutiny of the checks and balances within these ministries. Hopefully, this will reduce slippage, increase governance oversight, and keep the direction of policy on track. The durability of the GNU remains an area of concern, with the two largest parties still being ideologically different. It is concerning that cracks are already starting to emerge in the provincial structures, most notably the failure to reach an agreement on governing structure in SA’s economic hub, Gauteng.

The boost to sentiment from the GNU has been felt in asset prices as the risk premium in SA fixed income has seen a significant reduction. However, the SA economy still faces significant challenges and, although the direction of travel is positive, one cannot be hasty in moving long-term economic forecasts. Marginal positive revisions might be warranted at this stage, but the road to higher sustainable growth lies in the pace and minutia of implementation.

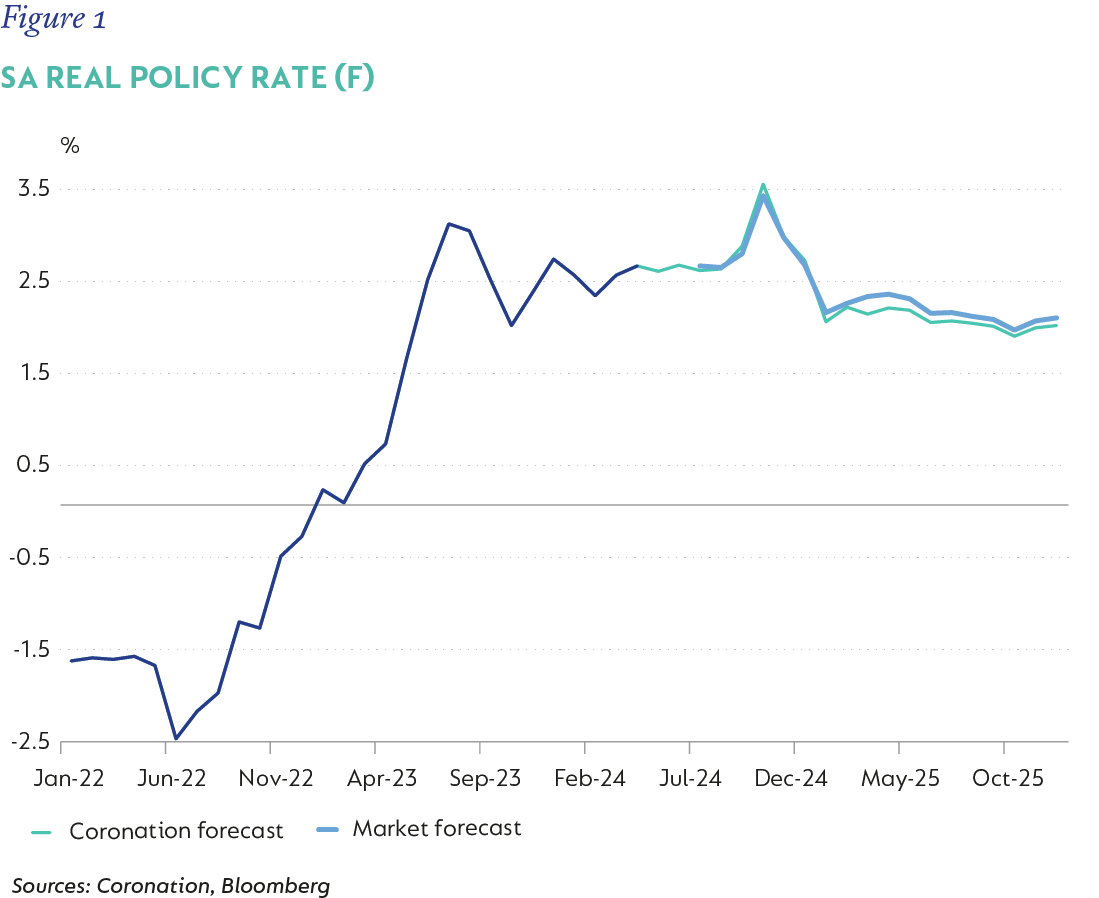

Inflation in SA has proven to be stickier than anticipated, but recent developments in food and oil prices combined with a stable rand have helped produce a slightly better outcome. Our expectations remain for inflation to dip towards the midpoint of the band (4.5%) in the fourth quarter of this year (Q4-24) and remain at or above 5% over our forecast period. The South African Reserve Bank’s (SARB’s) commitment to getting inflation sustainably on a path to 4.5%, the need to keep the real policy rates high amidst a higher-for-longer global rate environment and high fiscal risks implies a higher real policy rate than past experience. In addition, talk of moving the inflation target towards 3% will also weigh on the SARB’s ability to meaningfully provide monetary policy support to the economy. We continue to believe a real policy rate of 2%-2.5% remains appropriate in the current environment (Figure 1). This suggests a nominal repo rate of 7.5%, with rate cuts commencing in the third quarter of 2024 – in increments of 25 basis points (bps). However, upside risks to inflation remain from higher administered prices (Eskom will apply for a 44% tariff hike in 2025) and sticky food inflation. Market expectations of the repo rate have converged towards our expectations, with limited room for further compression.

SA registered a small primary surplus of 0.3% and a consolidated deficit of 4.9% (closer to 6% if we include Eskom support as an expenditure item as opposed to a transfer) in the 2023/24 fiscal year, but the outlook remains precarious. Firstly, the primary deficit required to stabilise debt is in excess of 1.5% and, secondly, the consolidated deficit is still a function of the difference between nominal growth and the country’s funding cost. On the second point, SA’s funding cost, even after the recent rally in bond yields, remains in excess of 10%, while SA’s nominal growth rate at best is at 7% (2% real growth plus 5% inflation). This gap can only be closed, through stronger real growth, as stronger growth lifts revenues, reducing the need to fund, thereby reducing supply in the local bond market, and bringing down bond yields.

Higher real growth can be achieved through more efficient and focused spending in sectors that promote longer-term growth, as well as reforms that unlock potential and bottlenecks in the economy. An optimist might say that the recent GNU outcome is bound to see an acceleration in this process, given the inclusion of pro-reform opposition parties. However, a realist’s view paints a slightly gloomier view. As outlined earlier, the ANC still controls the majority of the ministries, putting it in charge of 76%-78% of expenditure, while the DA only controls only 7%-8%, suggesting a very marginal (if any) benefit from better expenditure outcomes. Longer-term reforms are being enacted; however, the pace thereof remains sedate, suggesting that higher growth is out of reach in the medium term. This still leaves SA in the perilous position of accumulating debt at an unsustainable pace. There are financial repression levers that can be pulled to delay the day of reckoning, but if nothing is done with the extra time bought, the end result remains unpleasant.

THE FUTURE IS COMPLEX

The recent rally in SA fixed-income assets warrants a reassessment of the valuation metrics that drive the investment case for SA government bonds. As has always been the case, we prefer to glean the consistency of signals across a range of valuation metrics in order to draw our conclusions.

We start with our simple, top-down, fair value bond stack up, which is made up of the global risk-free rate (US 10-year) + [the SA – US inflation differential] + a SA-specific credit risk premium. We assign our long-term forecasts to each of the variables, which produces a result of 10.25% (4.25% + [5.5%-2.5%] + 3%), which compares to the current SA 10-year bond yield of 10.9%.

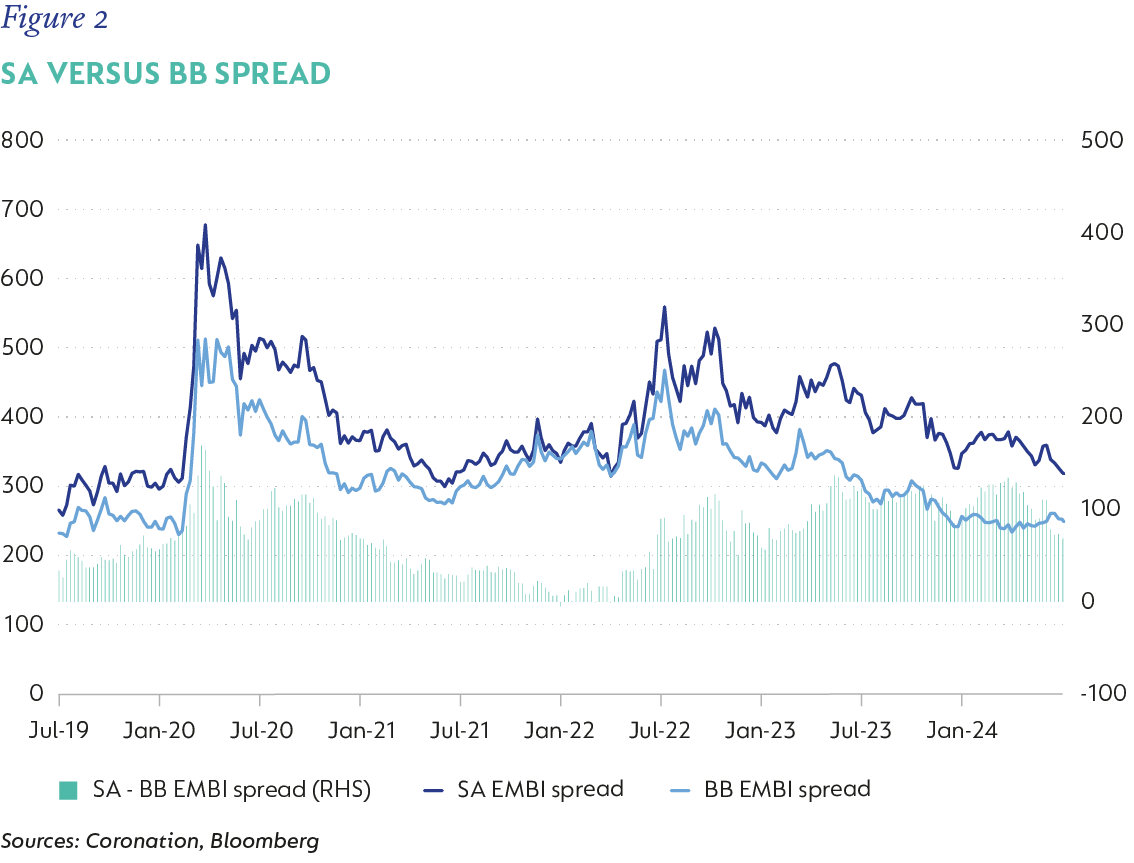

Next, we look at the performance of SA bonds relative to their emerging market counterparts, as represented in Figures 2 to 5. Firstly, we look at SA’s credit spread versus similarly rated peers (SA versus the BB spread[i]) which, at the current level of 69bps, is within 20bps to 30bps of its pre-Covid levels.

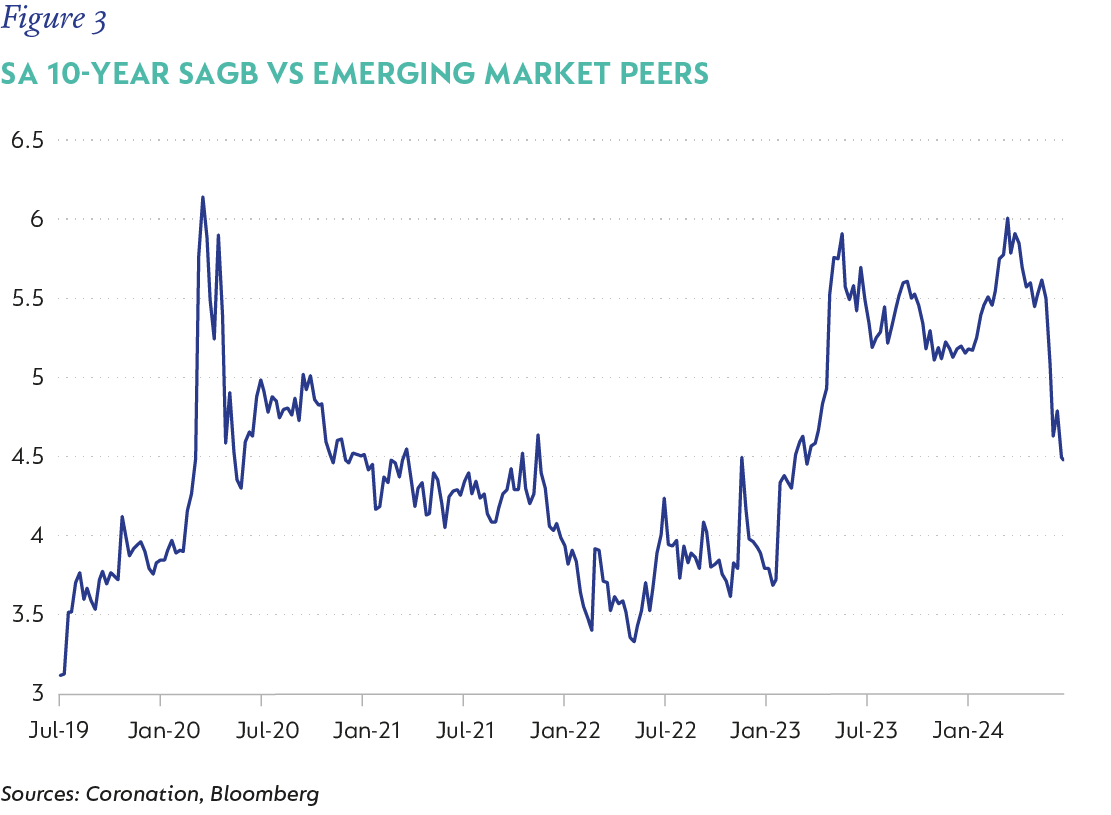

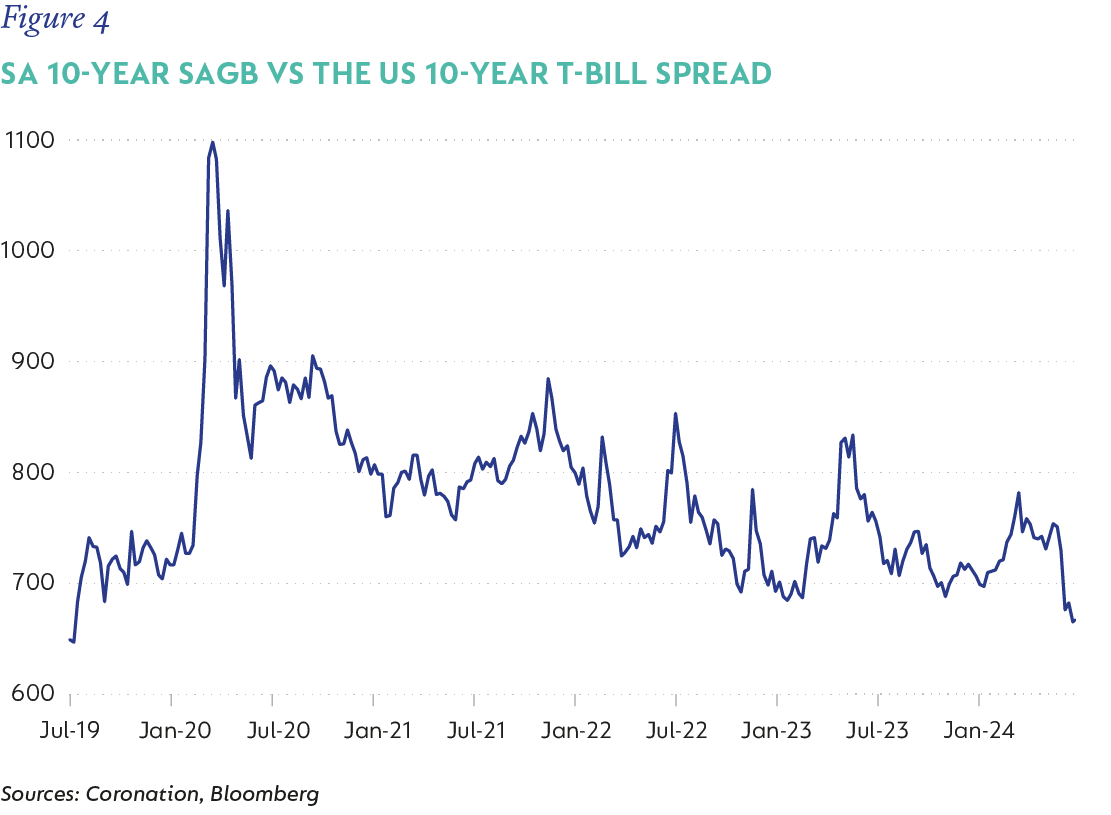

Next, we look at the SA 10-year government bond (SAGB) yield against its emerging market peer yields (representative by the Government Bond Emerging Markets Index) and the US 10-year Treasury Bill (Figures 3 and 4). Relative to other emerging markets, SA yields have seen significant compression since the formation of the GNU and now trade within 50bps of pre-Covid levels. However, compared to US yields, there has been significant compression to pre-Covid levels.

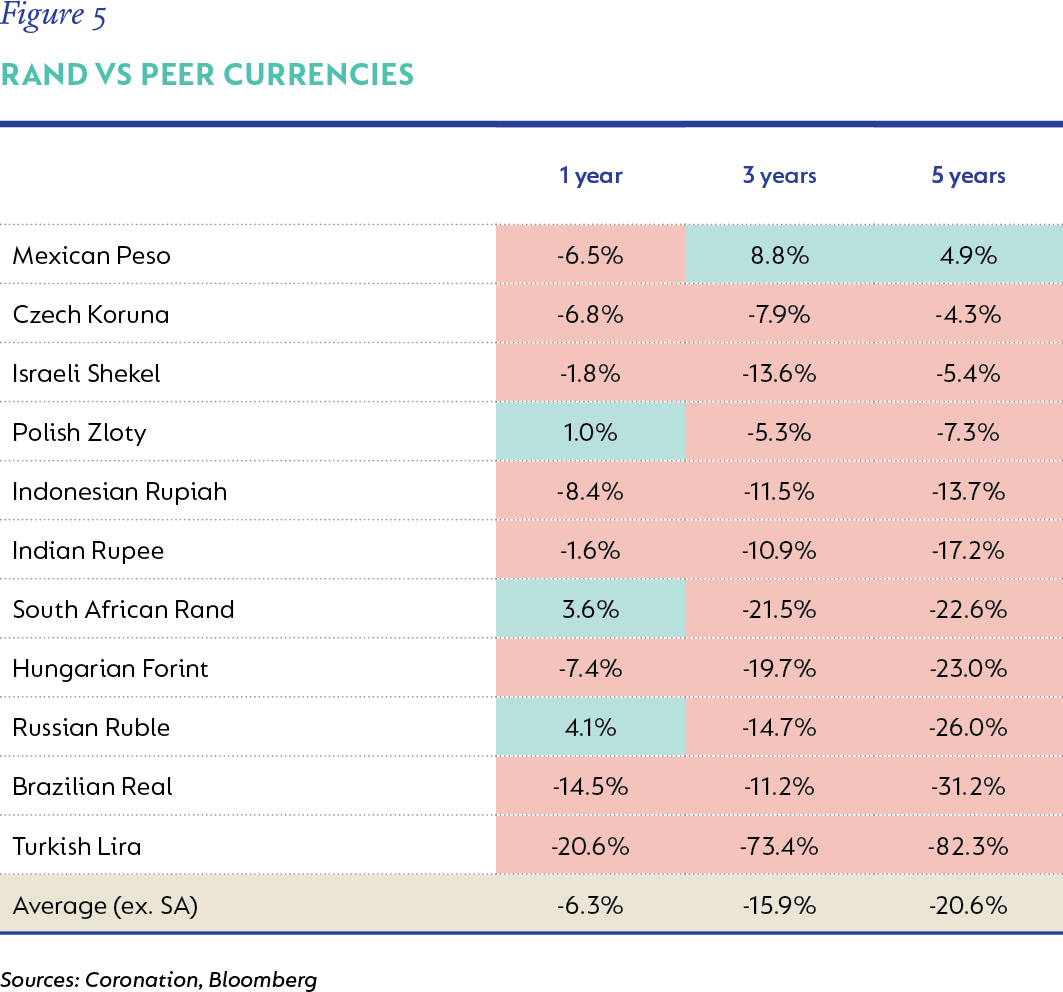

The rand has also seen a significant outperformance relative to its emerging market peer group over the last year (Figure 5). This has resulted in the long-term relative performance converging towards the peer group average, thus further eroding the embedded risk premium.

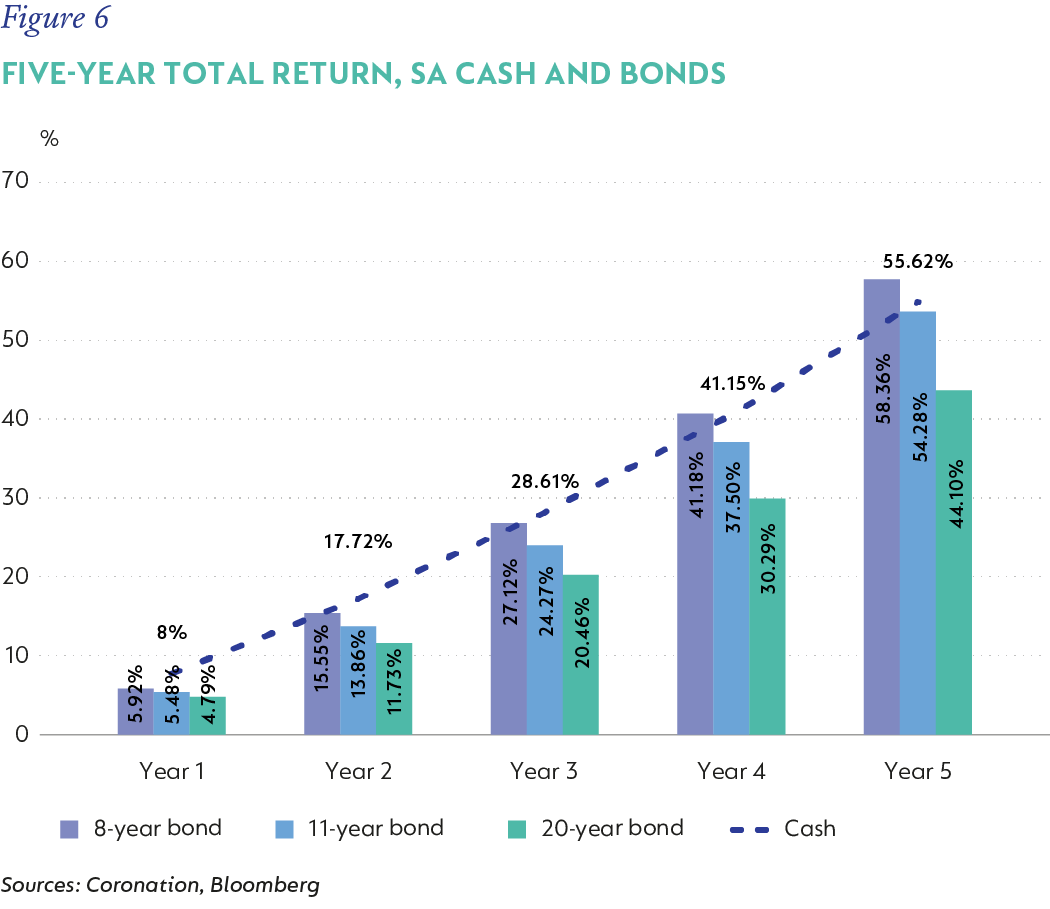

Finally, we look at a negative scenario, where bonds move wider by 100bps, each year for the next five years, to ascertain how much protection current yields offer. We compare the cumulative total return for various bonds on the yield curve relative to cash. Figure 6 shows that it is very clear that the margin of safety has narrowed significantly, with only the sub-10-year bonds offering protection in this negative scenario.

BETTER OUTLOOK, BUT ON TENTERHOOKS

The conclusion from the above analysis of both the standalone and relative valuations of SAGBs suggests the risk premium has narrowed significantly. There might still be 20bps-50bps of valuation uplift. However, in order for this risk premium to narrow further would require a shift in the underlying fundamentals with regards to either inflation or fiscal accounts. An outcome, which at this point, seems unlikely. We thus view SAGBs as being fairly valued at current levels.

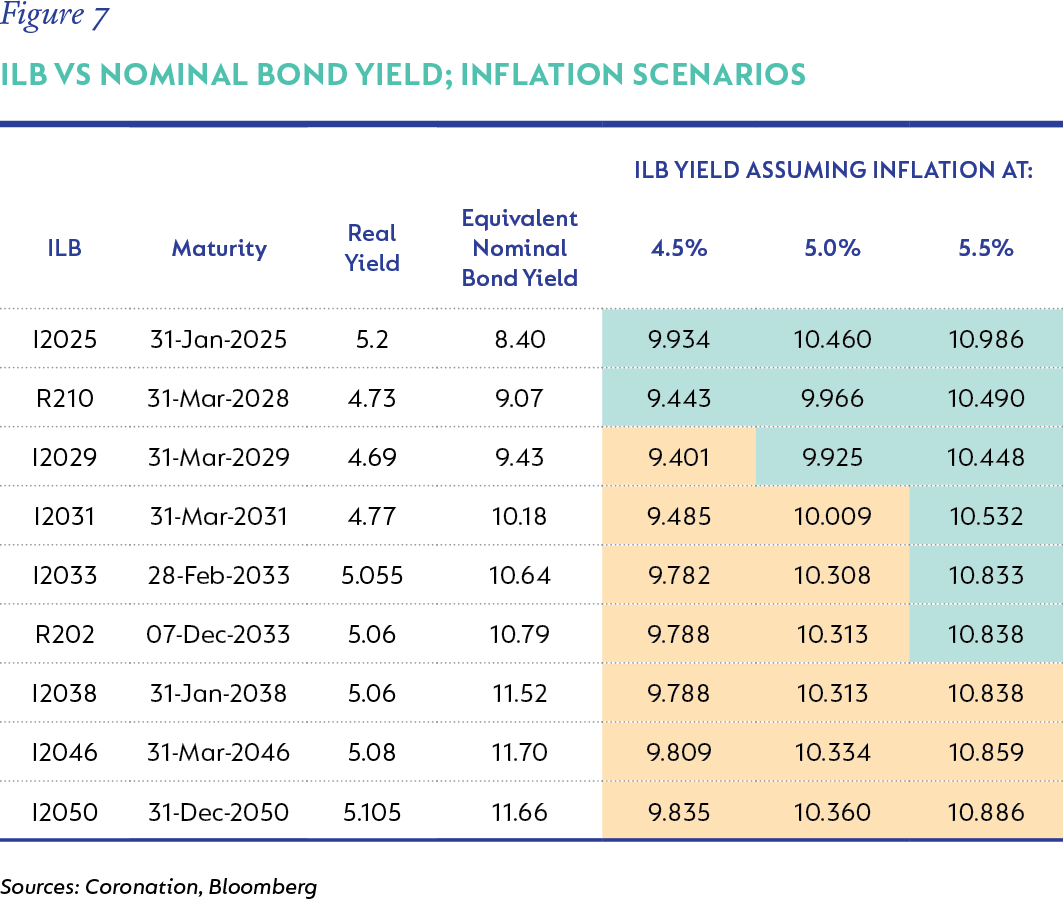

ILBs have significantly underperformed nominal bonds over the last year (9.1% versus 13.7%). This has put their longer-term performance approximately 2% behind that of nominal bonds (3-year: 6.9% versus 7.6%; 5-year: 6.4% versus 7.8%; 10-year: 5.1% versus 8.2%). However, at current valuation levels, ILBs are now starting to look quite attractive. Figure 7 shows the nominal bond yield for the equivalent ILB maturity and then the all-in nominal yield for the ILB using 4.5%, 5% and 5.5% inflation scenarios. The green cells highlight when the all-in nominal yield of the ILB is greater than the same maturity nominal bond. As a reminder, our expectation is for inflation to average between 5% and 5.5% over the longer term. It is clear from the below, that ILBs have become quite attractive, specifically up to the 2031 maturity (although, 2033, if we assume inflation averages closer to 5.5%).

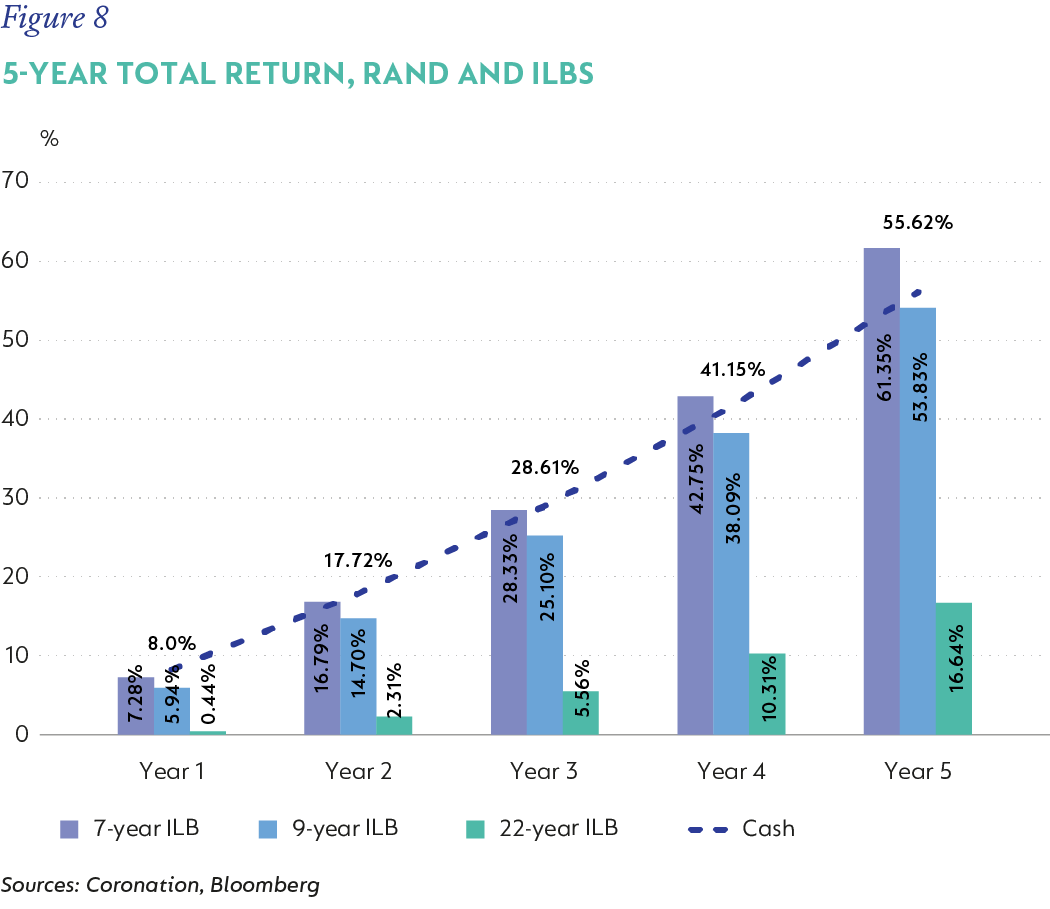

Next, we look at the margin of safety that’s provided by ILBs in a negative scenario, where they sell-off 75bps every year, over the next five years, with inflation averaging 6%, and then compare the total return of various ILBs relative to cash. Here again, ILBs up to a 7-year maturity (2031) offer significant protection relative to cash and a better return than even nominal bonds (Figure 8).

INTERDEPENDENCE

Global monetary policy remains conducive for risk assets, which should remain supportive of flows into emerging markets. SA has seen a significant reduction in risk premium following the formation of the GNU and the inclusion of the pro-reformist opposition into cabinet. SA inflation has benefited from both local and global factors and should support a shallow rate-cutting cycle starting towards the tail end of 2024. However, low growth, upside risks to inflation and burgeoning deficits will continue to weigh on the longer-term outlook for SA, unless reform implementation is accelerated. SA’s bond yields have seen significant compression, with the margin of safety narrowing significantly, both from an absolute basis and relative to the emerging market peer group. There might be slightly more juice left in the SA bond rally. But we believe that SA bonds now trade at or very close to fair value. A more positive shift in underlying fundamentals is needed to justify tighter valuations and outperformance. Thus, we would advocate positions closer to neutral in bond portfolios. The underperformance of ILBs in the recent SA fixed income rally has increased their attractiveness, which warrants a generous allocation, focused on maturities of less than 10-year maturity, even ahead of nominal bonds.

[i] BB is a non-investment grade rating, indicating a higher risk of default compared to investment-grade securities

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal