Stewardship & ESG

Tackling water security

Last year in May, Marie Antelme covered South Africa’s water crisis, with a deep dive into the pain points and responsible agencies. This concern has not abated and has grave consequences for SA and its citizens. Our 2023 Stewardship Report covers our ongoing analysis of SA’s water crisis and how our investment team is addressing it in the context of investments.

The Quick Take

- SA’s water crisis is multifaceted, encompassing SA’s river topography and catchment areas, rainfall distribution, climate change, infrastructure and supply chain management

- We have analysed the JSE Top 100 and identified the companies most exposed to water-scarcity risk

- Based on this analysis, we have initiated ongoing engagements with a subset of companies to understand their practices and promote adequate mitigation of these risks

Water security is arguably one of the most critical risks to South Africa’s social, economic, and political long-term future. In particular, water stands as a critical business imperative, indispensable for a myriad of functions including employee-related health and sanitation, as a direct input into business processes, and various aspects within the company’s supply chain.

The water security challenge varies across businesses, as water is both a local and national resource and because the availability of both the quality and volume of water required for operations differ depending on the region of operation and nature of the business.

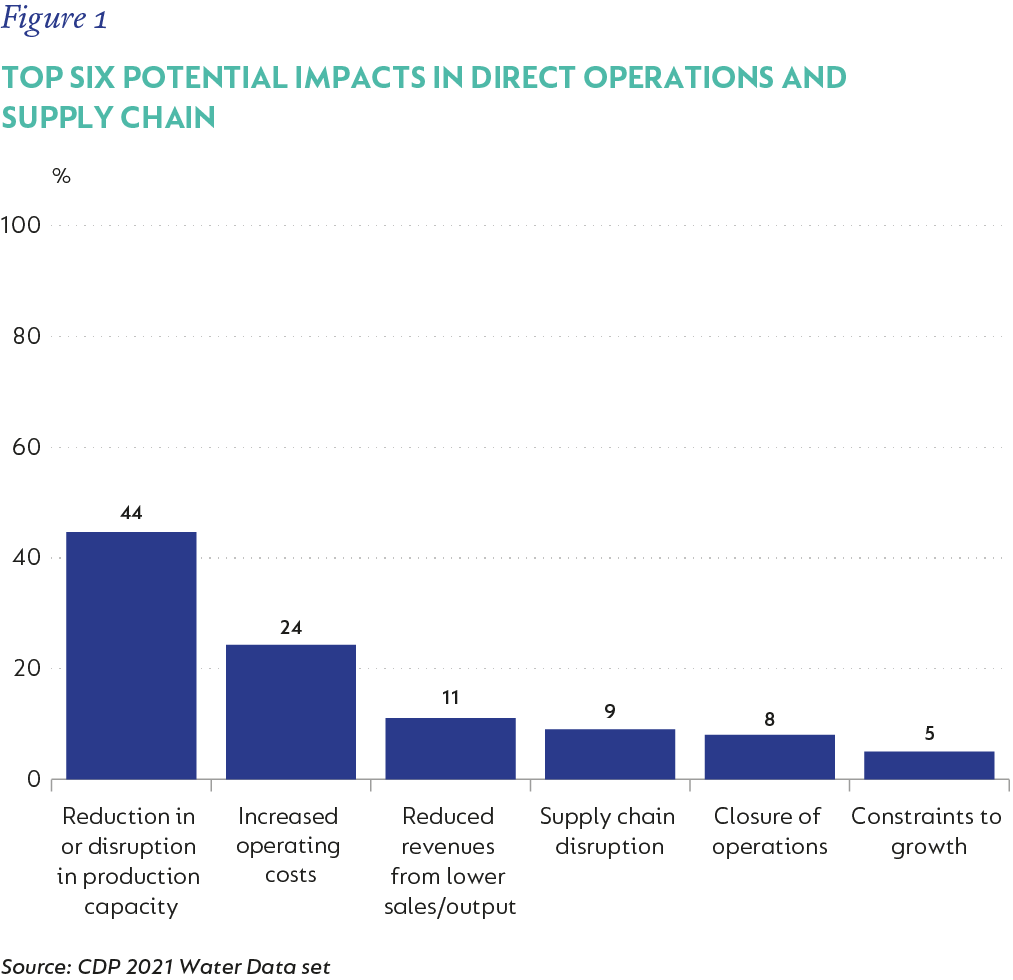

Figure 1 illustrates how water stress can impact a company in several ways. As insufficient water security is a systemic risk for many South African businesses, we identified this as a thematic area of focus for engagements in 2023 and 2024.

A COMPLEX AND MULTIFACETED CHALLENGE

Our engagement project must be contextualised within the operational landscape of South African companies. Understanding the broader context is paramount in addressing the challenges faced by businesses in South Africa. Businesses face the dual dilemma of water stress exacerbated by climate change, as well as municipal infrastructure challenges which are affecting the availability of sufficient, useable water that may be required to run a business.

Water security is not a simple issue in South Africa. Not only is South Africa a water-scarce country, but the supply chain from source to tap is complex. It comprises many integrated systems, and the regulatory framework that governs its operation as well as its oversight is complicated and problematic. While water as a resource is a national asset, regulated by the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS), the provision of municipal water – which is what most companies rely on – falls under the purview of local government.

The legislation that governs the two entities is different, and one department cannot interfere with the workings and obligations of the other – in other words the Minister of Water and Sanitation cannot easily intervene in the delivery of water services at local government level. Likewise, local governments cannot allocate water resources without going through the processes required by the DWS.

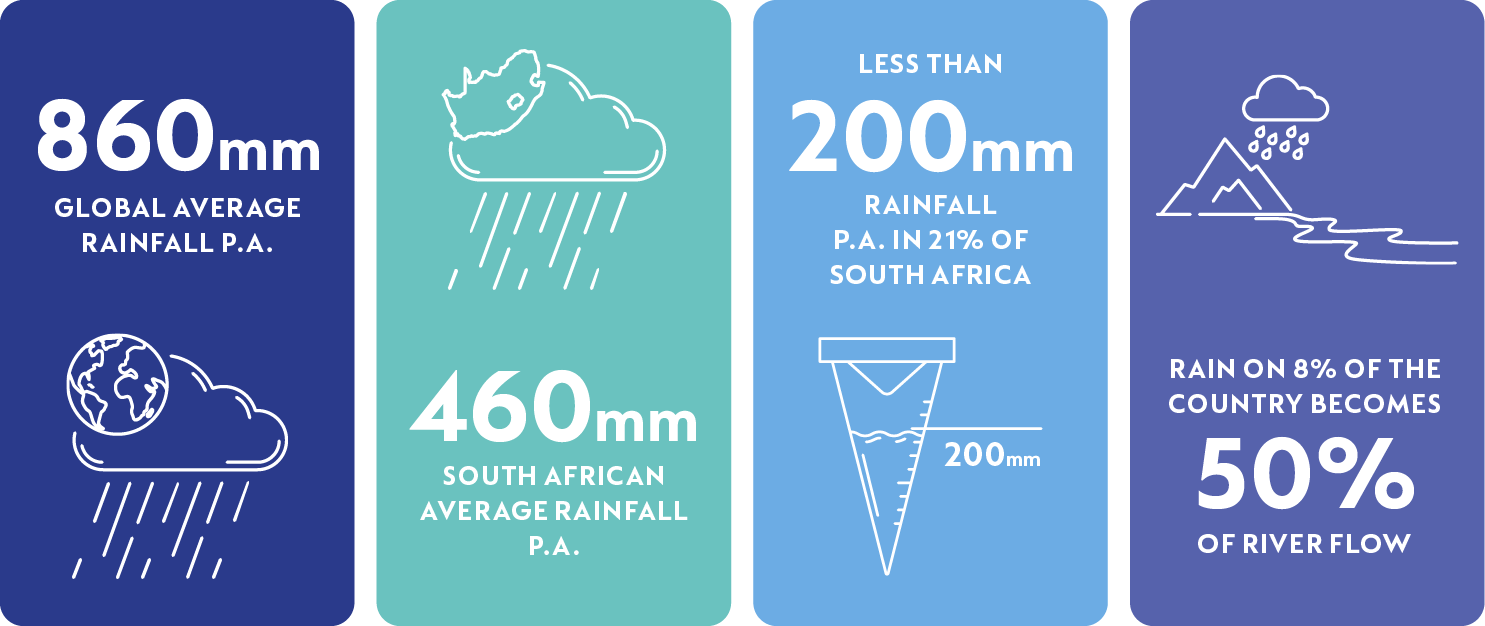

Using a wide lens, South Africa’s biggest long-term water challenge relates to inherent scarcity and the impact of climate change. Annual average rainfall is around 460mm, which is almost half the global average of 860mm. This rainfall is very highly concentrated and unevenly dispersed across South Africa’s landmass, with 21% of the country getting less than 200mm per annum. Rain which falls on 8% of the land contributes 50% to what ultimately becomes river flow and can be abstracted.

In addition, South Africa has no navigable rivers, which are traditionally critical to economic and industrial development because they provide a natural source of necessary water and transport. The larger rivers – the Orange, Vaal, and parts of the Limpopo – occur in parts of the country where there is little industry, while South Africa’s commercial and industrial heartland – Gauteng – has no sustaining water source. Seven out of nine provinces rely on water from other provinces for around 60% of their economic activity. Gauteng is 100% reliant on water from elsewhere. This increases the vulnerability of South Africa’s economic heartland to water scarcity and climate change.

The processes which are necessary to sustain and maintain these systems are also at risk. Water monitoring and measurement at source has seen three decades of reduced fiscal and human resources, as people are needed to monitor rainfall, river flow and groundwater at source regularly and over long periods of time. Most of the larger rivers are dammed to capacity. Maintenance of and investment in the engineering of these ageing systems has been poor.

However, the very weakest part of these complex systems is right at the end of the supply chain. Population growth, coupled with water scarcity and climate change have increased the strain on water resources and infrastructure, but this has been materially exacerbated by the poor performance of entities tasked with maintaining water and sanitation infrastructure. The widespread breakdown in governance at the municipal level has exacerbated poor maintenance of water systems leading to polluted systems, poor treatment and massive physical and revenue loss (non-revenue water).

Water stoppages are increasingly common, and “water shedding” has become common in most geographies outside of the Western Cape. According to the Water Research Commission, 36.8% of total municipal water supplied in South Africa is lost before it reaches industries and households. The physical impacts of climate change are predicted to worsen and will disproportionately affect different regions. Average temperatures in the South African interior are projected to increase at 1.5 to 2 times the rate of increase of global average temperatures[1].

Rainfall is predicted to increase over certain regions of the country and decrease over others, potentially causing droughts and floods, each with detrimental impacts on society. Flooding can compromise water quality with excess water flow collecting contaminants and polluting the water supply[2] . Water treatment systems, already under immense strain, are likely to further restrict both availability and usability for certain purposes. Periods of drought will have meaningful impact on South African society, not only impacting the quantity of water available for human use, but also water quality as pollutants in the water become more concentrated[3].

DEEP DIVE TO ASSESS THE SCOPE OF THE WATER CHALLENGE

In 2023, we examined the Top 100 companies listed on the JSE to identify major water consumers, identifying 58 firms for a closer analysis of their water-related risk exposures and management strategies. This included compiling data on specific aspects, including water consumption metrics, strategies for water usage reduction, risk management practices, water reduction targets, exposure to geographic areas with high water stress, and any penalties related to water usage. Our initial approach involved reviewing company-provided water disclosures to ascertain whether this adequately addressed the questions posed above. Where further information was needed, we engaged with each company seeking additional details. This effort resulted in 25 water-related interactions across 20 companies since the start of 2023.

INITIAL FOCUS ON DISCLOSURE AND PROCESSES

In 2024, we are moving into the second phase of the project. We aim to analyse the data collected from the initial assessment and compile a targeted sub-list of companies that either lack adequate disclosure on water usage and risks or do not have sufficiently robust processes in place to manage these risks adequately. We will prioritise companies based on several key factors, including the volume of water consumption, the geographical location of operations with potential water stress issues, and sector-specific water usage norms and risks. Our aim in these engagements is to request increased disclosure and explore improved processes to better manage water-related risks.

Read our full Stewardship Report here.

[1] Climate change – detailed projections for future climate change over South Africa, greenbook.co.za

[2] National Geographic, How Climate Change Impacts Water Access, https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/how-climate-change-impacts-water-access/

[3] UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, The impacts of drought on water quality and wildlife,

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal