Investment views

China: Looking ahead post-stimulus

Navigating investment opportunities in the wake of recent policy measures aimed at economic recovery

The Quick Take

- China offers attractive investment opportunities in leading technology and consumer-facing businesses with compelling valuations compared to alternatives in the US and India

- Investor sentiment toward China has been in a downward spiral, where negative news sparked sell-offs, further driving prices down

- The recently announced stimulus package by the Chinese government aims to rejuvenate the economy and break this cycle of pessimism

- We hold positions in market-leading businesses poised to benefit from improved consumer confidence as the economy recovers

China’s extraordinary economic rise over 35 years, beginning in 1985, is one of the most remarkable achievements in modern history. The country’s rapid expansion in the late 20th century lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty and fundamentally reshaped the global economic landscape. However, in recent years, many Western investors have grown disillusioned with the state of the Chinese economy and its political direction. To fully understand the current investment landscape following the announcement of this new stimulus package, it is important to not only evaluate the policy measures and the attractiveness of Chinese businesses but also to reflect on the historical context of China’s extraordinary rise and its proven ability to defy expectations.

THREE DECADES OF GROWTH

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took control of mainland China after defeating the nationalist Kuomintang party in the civil war that followed World War II and the withdrawal of the occupying Japanese army. By the time Deng Xiaoping took over as leader of the CCP in 1978, China had experienced 30 years of no real economic progress. At the time, China accounted for less than 2% of global economic output – making it largely insignificant on the world stage. According to the World Bank, GDP per capita was approximately $160, compared to $10 500 for the average American (65x higher). Deng’s economic reforms took a few years to fully take hold, but the abandonment of strict communist economic dogma in favour of wealth creation (Deng famously said that “getting rich is glorious”) resulted in economic growth accelerating at the same time that population growth was slowing down, partly due to the implementation of the “one child” policy. From 1985 onward, China’s GDP per capita grew by 6% or more almost every year until the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

Over more than three decades of sustained growth, China not only lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty but also emerged as the world’s largest economy in terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)[1]. Even using market exchange rates, China remains the second-largest economy, accounting for 18% of global output by the end of 2023 – up from just 2% in 1978. For comparison, the US accounted for 25% of world output at market prices in 2023. While India has also achieved impressive economic growth since it launched its own reforms in the early 1990s, it still only accounts for a mere 4% of world output. The key takeaway is clear: what happens in China has a significant impact on the global economy.

TRAPPED IN A CYCLE OF NEGATIVITY

Despite China’s importance, Western investors have become increasingly disillusioned with the “China story” in recent years. Rising tensions with the United States, where there is bipartisan consensus that China’s exports have hurt employment in the local manufacturing sector, have resulted in both tariff and non-tariff barriers being imposed on Chinese imports. The current US presidential election campaign has been marked by anti-China rhetoric from both candidates, differing only in the extent to which they want to raise trading barriers further.

China’s strong relations with stridently anti-Western nations like Russia, Iran and North Korea, coupled with its heavy investment in future-focused technologies, such as electric vehicles and artificial intelligence, have prompted the US to impose widespread export restrictions on sensitive technologies, particularly cutting-edge chips, in an effort to prevent China from closing the gap with Western tech companies. While the political reasoning behind these measures is evident, the economic case is less compelling. The US runs bilateral trade deficits with over 100 countries – a consequence of its large budget deficits and insufficient domestic savings, rather than trade imbalances specific to China.

These dynamics have played out against the backdrop of China’s slowing economy. It was the last major economy to lift Covid-19 restrictions, and the subsequent economic recovery has been brief. Decades of over-investment in the property market have resulted in an oversupply of properties (both finished and unfinished), causing real estate prices to decline for several quarters. Since residential properties represent the largest source of wealth for Chinese citizens, economic sentiment has inevitably suffered when prices have fallen, especially as the values of outstanding mortgages have not decreased with property prices.

Adding to the challenges, China’s population has likely peaked, with more deaths than births being registered in the last two years. The population decline is expected to continue in the coming decades as the fertility rate for women is currently half of the rate required for a stable population. This “demographic crunch” mirrors trends across East Asia – Japan, Taiwan and South Korea have similar or lower fertility rates. However, unlike these three peer countries, China has not yet attained its goal of becoming a high-income country. This phenomenon is often described as “growing old before getting rich”.

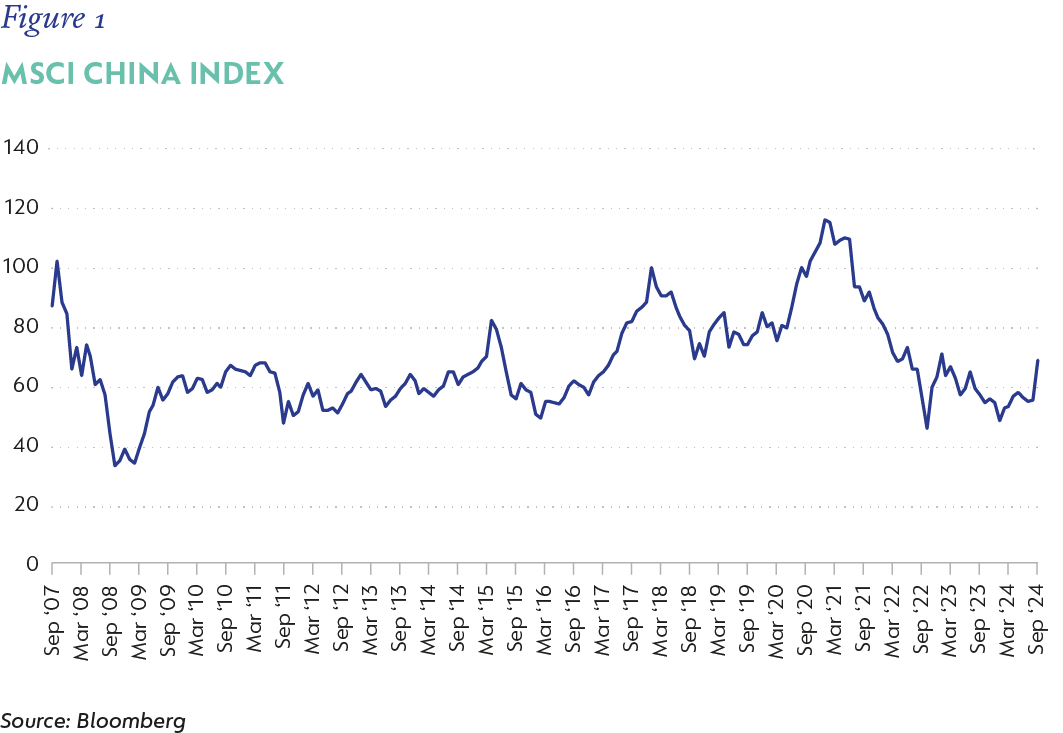

As a result, Chinese shares accessible to Western investors have been trapped in a vicious cycle: disillusionment with the state of the Chinese economy and its political direction leads investors to sell their Chinese shares, and each bout of negative news drives share prices down further, fuelling fear and triggering even more sell-offs. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the sharp decline of the MSCI China Index (a widely tracked China benchmark) from its peak in early 2021, and how this has reduced China’s weighting in the broader MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Meanwhile, markets like Taiwan and India have performed far better on a relative basis.

POLICY MEASURES AND ROOM FOR RE-RATING

Escaping this negative cycle has become a top priority for the Chinese government. In late September, the authorities announced a series of unprecedented measures to improve domestic sentiment and support the economy and consumers. Large-scale support for the real estate market was a key announcement. Measures included lowering lending rates, reducing down payment requirements for second homes from 25% to 15%, and providing financial assistance to allow state-owned enterprises to buy unsold inventory from property developers.

For consumers, promoting consumption was highlighted as a priority, along with measures to increase salaries for low- and middle-income earners. Unlike the US’s inward-looking approach, China also pledged to encourage foreign investment in its local manufacturing sector.

The total value of the announced measures, also including support for the stock market, exceeded two trillion RMB ($280bn). Further fiscal support and capital injections into large banks have followed. Some economic commentators have likened this series of announcements to the 2012 “Whatever it takes” speech by Mario Draghi, then President of the European Central Bank, which played a crucial role in stabilising the Eurozone during the sovereign debt crisis following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. However, this comparison may be overly optimistic; while stimulus can provide short-term relief, it rarely addresses long-term structural challenges.

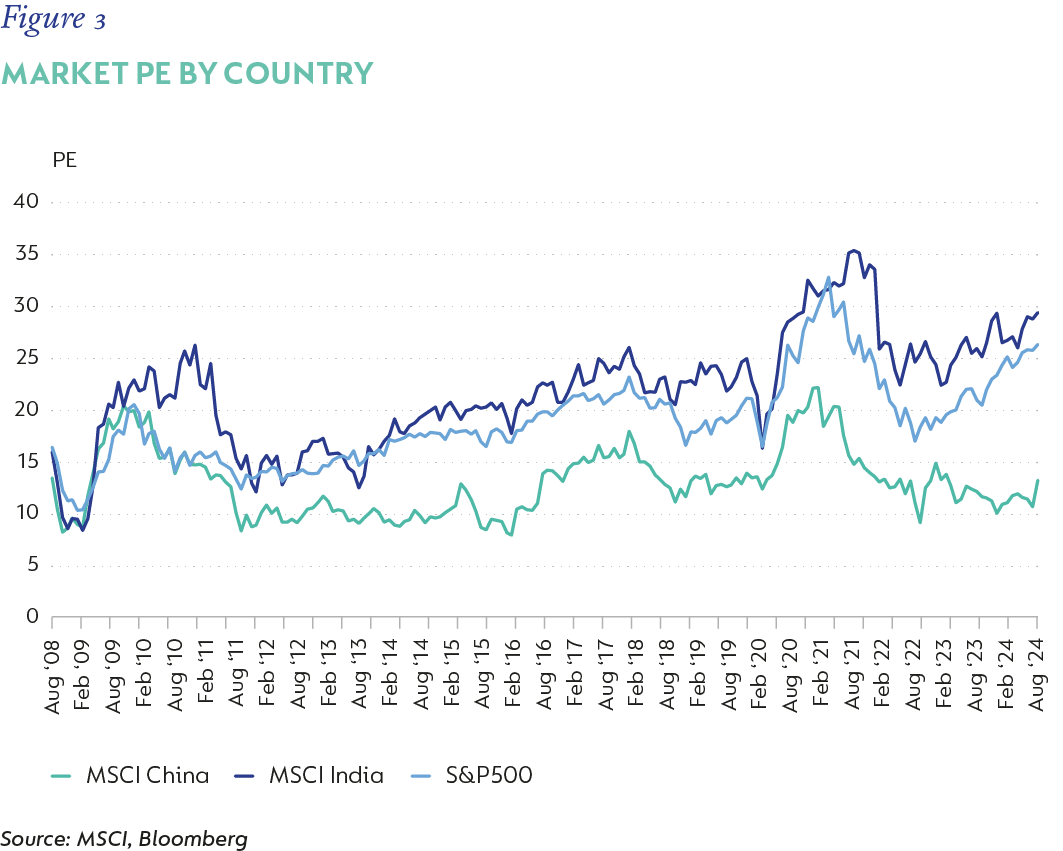

Despite the sharp rally in the Chinese markets following the announcements, there is still room for further re-rating. China has underperformed US and world indices over all longer-term time periods and valuations remain relatively low compared with historical levels. The market price-to-earnings ratio is only around 13x, a substantial discount to the US market (S&P 500) and India, which was until recently a big beneficiary of capital flows leaving China (Figure 3).

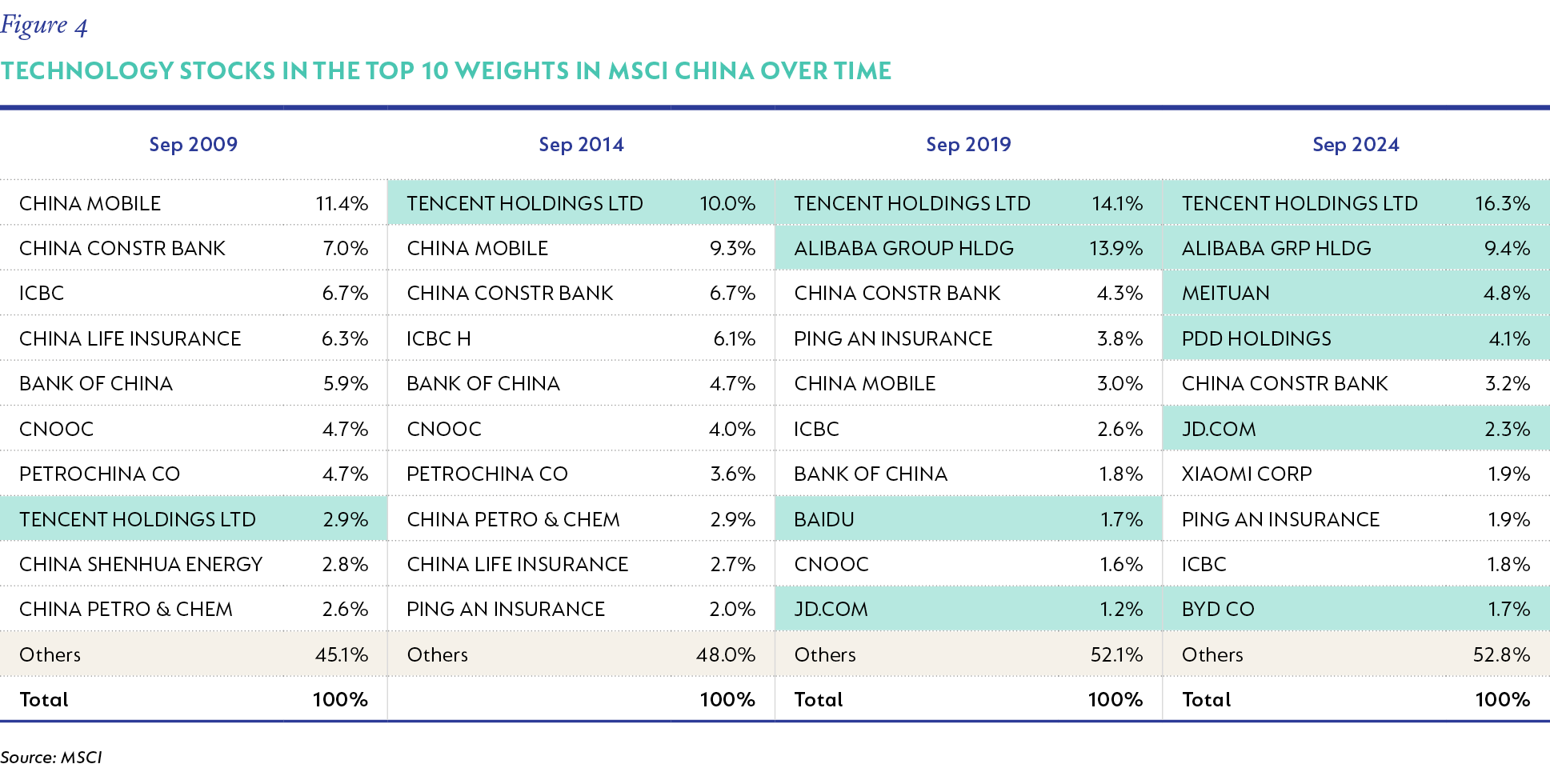

Over time, we expect the multiple and hence valuation of the Chinese market to rise, as higher quality businesses with more durable moats gain prominence in the index. This trend could mirror the experience in the US market, where the S&P 500’s PE multiple has increased as the “Magnificent Seven” technology stocks grew to dominate the index. Figure 4 illustrates this evolution in five-yearly increments since 2009, highlighting the rise of the “new economy” stocks (businesses driven by modern technology) – that typically attract higher through-the-cycle multiples. By the end of September 2024, six of these stocks accounted for nearly 40% of the benchmark, underscoring their increasing influence.

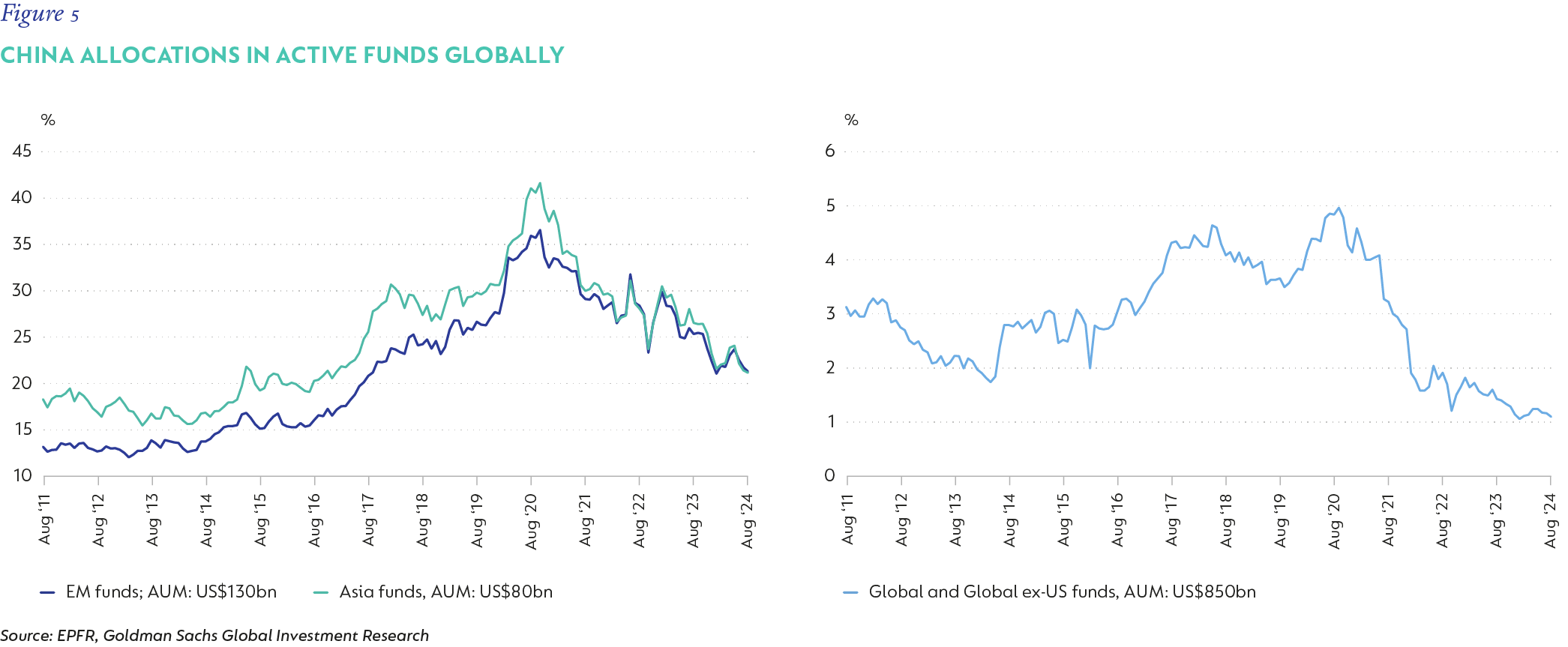

Further buttressing the case for a potential upward re-rating is the sharp decline in active weight for Chinese equities in specialist emerging markets and in global funds (Figure 5). Chinese equities are therefore under-owned across the board in active funds, and the recent moves have largely been driven by investors reversing this underweight position.

RETIREMENT REFORMS TO ADDRESS DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES

In addition to economic stimulus, China’s authorities have introduced critical structural reforms to tackle demographic challenges impacting the workforce. Currently, the retirement age for women in blue-collar jobs is only 50 years old, 55 for women in white collar jobs, and 60 for men – ages set in the 1950s when China’s life expectancy was only 65 years. With life expectancy now at 78 years – on par with the US – a change was inevitable. Under the current system, workers could conceivably contribute to pensions for as little as 20 years and draw benefits for many more than 20 years after retiring.

Starting in 2025, China will gradually raise the retirement age across all categories, extending the working life of adults and alleviating the strain of an ageing population on the labour force. By contributing to pensions and social security for more years and receiving benefits for fewer years, the sustainability of the overall pension system will improve significantly.

It is notable that attempts at raising the retirement age in Western Europe – which faces similar challenges with ageing societies – have resulted in considerable political upheaval. In China, these unpopular measures will be implemented with little room for public dissent. Further reforms aimed at reducing youth unemployment (which is estimated to be between 20% and 25%) are also being introduced, with wage subsidies and training allowances to encourage businesses to hire and train young workers.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ACTIVE INVESTORS

As equity market investors, our primary focus is on the long-term earnings prospects of the businesses we own on behalf of our clients. We want to own the best businesses in China that can be bought at a reasonable price and that will thrive with or without stimulus. Following the recent market movements, the Coronation Global Emerging Market Equity Strategy now has approximately 30% exposure to China, held across a selection of stocks that we believe are positioned to be long-term winners in their respective industries. Despite recent share price appreciation of 30-50% following stimulus announcements, at the time of writing, these holdings remain very attractively valued relative to historical averages and global peers.

For example, the e-commerce giants JD.com (3.7% position) and Pinduoduo (3.1% position) collectively control around 40% of China’s e-commerce market. JD.com trades on just 11x forward earnings and holds 40% of its market capitalisation in cash. The company has significantly stepped up capital returns and is expected to maintain this trajectory. Pinduoduo, trading at 10x forward earnings, is expected to grow earnings at 15% annually as its international operations narrows losses. By comparison, Amazon.com in the US trades at 29x forward earnings.

We also hold a 2.3% position in Trip.com, the clear leader in China’s domestic online travel market (covering hotels, flights, trains and more) and the leading provider for international package tours for Chinese tourists. Additionally, we hold a 2.1% position in Tencent Music, the leading streaming platform in the country, which charges subscribers just $1.50 per month – the equivalent of a cup of coffee – for its normal offering. Our largest position, however, is the indirect exposure to Tencent, the leader in gaming and social media, which trades on only 16x earnings. Our exposure to Tencent is mainly held via Naspers and Prosus (a combined 5.4% position), which trades at a 35% discount to the value of their 24% stake in Tencent. Moreover, assets like Delivery Hero, Meituan and Swiggy (India’s food delivery platform) are effectively being valued at zero.

Beyond e-commerce and tech, the Strategy’s exposure to China also includes investments in sectors such as sportswear, food delivery, quick service restaurants, casinos and electric vehicles, all trading at reasonable forward multiples (10x to 17x earnings). Most of these companies have strong balance sheets with significant cash reserves, and all are likely to benefit from improved consumer sentiment as the economy recovers.

While there are undeniable risks to investing in China, we believe that through careful stock selection, our China exposure will generate significant returns for our clients over time. Although the market is much smaller, a comparison with South Africa is quite informative. Despite 15 years of economic stagnation, the rand declining with more than 50% and a contraction in GDP per capita, the winning businesses in South Africa have delivered stellar dollar returns to investors. Shares such as Clicks, Mr Price, Bidvest, AVI, First Rand and Advtech have each delivered annual returns of 10.4% to 17.2% over the past 15 years, resulting in shareholders earning cumulative returns of between 440% and 1077%. The weighted average upside across our Chinese holdings is estimated at 70%, substantially ahead of the 45% weighted average upside of the rest of the portfolio.

[1] Lower income countries like China tend to have a far lower cost of living than higher income countries like the US. PPP attempts to overcome this by converting local prices into dollars using an exchange rate that reflects the difference in the cost of living. As a simple example, if China’s cost of living was half that of the US, then instead of converting China’s local currency GDP at the official exchange rate of +/- 7 RMB per dollar, the PPP calculation would use an exchange rate of +/- 3.50 RMB per dollar. The PPP GDP of China would then be double that of the official US dollar GDP.

Global (excl USA) - Institutional

Global (excl USA) - Institutional